Here’s the plan: I’m going to shamelessly romanticize a cake in this post. I’m going to say that a cake is not always just a cake – as in the culmination of flour, butter, eggs, and sugar – but that a cake can be more than just a cake. I’m going to tell you about one particular cake and how it’s not just a cake but something meaningful enough to change someone’s direction in life. Then I’m going to turn around and tell you that this is a cake that, after all is said and done, is a delicious cake.

Please let me take you to a lesser known corner of Bangkok whence this cake comes while you’re trying to grasp the gibberish profundity that is the previous paragraph. Here, gimme your hand. You look a little discombobulated.

I could be writing one blog post a day for the next ten years focusing on nothing but the food of my hometown, Bangkok, and I am convinced that at the end I still won’t come anywhere close to running out of things to say. For every story I tell you, there will be at least two related stories brewing and bubbling in my head. And in the course of studying one thing deeply enough to be able to share my findings with you, I know a few new discoveries are waiting to be made.

Bangkok is an endless book that keeps you on your toes. Just when I think I know the story, new things pop up, forcing me to go back a few pages – or chapters – looking for missed clues. The community around Suan Phlu Masjid (มัสยิดสวนพลู) in Thon Buri is one of the clues I had missed all these years.

Had it not been for a writing assignment for a publication, I doubt I would’ve found myself on Soi Thoet Thai 19, a ridiculously narrow, barely navigable, can’t-even-bribe-a-cabbie-to-enter street where I’d never been my whole life. Running parallel to a train track and lined with wooden houses behind corrugated metal fences and patches of unruly swamp plants, this is not exactly a street meant for leisure strolls.

Yet, strangely, I felt right at home. It could be because the people were so nice to me. I must have been emitting the disoriented stray dog vibes that belied my tough city girl’s face for every passerby seemed to know that I wasn’t from the area and offered directions even before I asked for them.

Good thing everyone knew the small home bakery I was looking for. All I had to say was, “Badin cake” (“ขนมบดิน”) and all hands pointed in one direction.

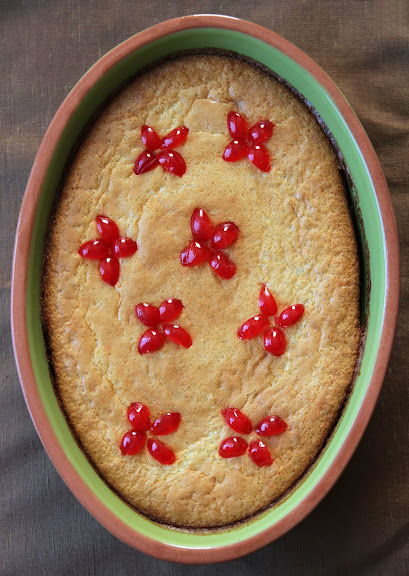

Mariyah Bakery (มารียะห์เบเกอรี่) doesn’t look like much. It’s a nondescript house that I could have easily walked right past had it not been for the fragrance of freshly baked cakes that wafted through the air. The set-up was also basic: trays of golden-colored cakes were set out on a large table right out front. A few auxiliary products in cellophane bags were kept in a glass display case.

As Mariyah Yokyorkhun, the owner of this bakery, was chatting with me, her husband stayed close by, helping, setting up the shop, greeting customers. What a beautiful couple. Though a part of me tried to stay neutral, another part of me already liked my interviewee before I sat down.

Mariyah explained to me that Khanom Badin or Badin cake is a butter cake that had been enjoyed mostly during special religious occasions by members of various Thai-Muslim groups (including this one in Suan Phlu Masjid area) for decades. The etymology of this cake’s name, “ba-din,” remains a mystery. It’s clearly not Thai; nor does it appear to be rooted in Arabic. There’s a theory being circulated about how this cake was named after the clay pot (mo din) in which it was originally baked (supposedly). The theory maintains that the name “mo din” subsequently went through a phonetic change and became “ba din.” (Personally, I don’t buy it. But that’s neither here nor there. All we know is that this is a cake that has been a staple among Thai Muslims for ages.)

Then, about 40 years ago, Mariyah’s mother came up with what she believed to be a unique version of this cake, employing a brand of imported clarified butter that, according to Mariyah, had been used within the Muslim community exclusively in savory dishes prior to that point. The cake became a hit among members of the community, and a bakery was born.

“This is all my mother had,” said Mariyah of the cake. “This cake kept us housed and fed and put me through school – it was all we had and she passed on to me this inheritance.” And with that, I knew this story had no chance of being objective.

Though growing up with it, Mariyah had never planned on taking over the bakery. That is until she was about to finish her journalism program in college when her mother passed away. After some reflection, the young woman made a decision not to pursue a career in television and broadcasting and take over her mother’s bakery instead. It was a tough decision that, after two decades, is now starting to pay off. The bakery has in recent years been getting the attention of the Thai media and seen a steady increase in sales.

Back in her mother’s time, though the cake had attracted enough regular customers in the area, the business could hardly be called a success. “Mom worked hard every day but never knew what it’s like to see our bakery grow and succeed,” said Mariyah. That’s changing. People are on to the delightful little secret of this obscure nook of Bangkok now.

The bakery is still small in size and Mariyah has no immediate plan to expand it. “It’s a family business and we want to keep it real,” she said. “Quality control is easier that way.” Besides, both the bakery and Badin cake have been so deeply rooted in the community around the masjid that even the thought of having her flagship product mass-produced and sold at chain convenient stores around the city fills Mariyah with dread.

But she hoped to grow; the direction just wasn’t clear. In the meantime, she enjoys waking up long before sunrise to make this cake just to do the same thing again the next morning.

That was supposed to be the extent of my coverage on Badin cake: a cake that’s more than a cake, an interesting product by interesting people with an interesting story.

Then I tasted that cake. And goodness gracious great balls of fire. The hearty texture. The strong buttery scent and taste. I knew I had to learn to make this delicious cake.

What purports to be the recipe for this cake as made by Mariyah Bakery was published in the 6th volume (no date of publication given) of a pocketbook series called Chong Thang Tham Kin (ช่องทางทำกิน). The recipe calls for one kilogram of flour, 25 eggs, 5 (14-ounce) cans of sweetened condensed milk, one kilogram of sugar, 400g of butter, and “a little bit of vegetable oil.” This ratio is supposed to yield about four 10×10-inch trays of Badin cake (pp. 50-51).

I checked with Mariyah and she said that was just an approximate. “There’s much more to the process than the ingredient ratio,” she said, revealing — understandably — no further than that.

Encouraged by some Thai-language blogs documenting their success with this formula, I tried making the cake according to that ingredient list (scaled down five times) and the procedure detailed in the previously-mentioned pocketbook throughout March 2012. By April 2012, after a series of pasty and dense cakes (see the pictures here and here), my trust in humanity lessened a bit. You could say I’m a bad baker who can’t follow instructions, but if my opinion means anything, I think something was amiss.

Then I discovered this video clip which features Mariyah and her bakery on a Thai television show, Food Diary, and things became clearer. Though I’m still confused on a lot of things surrounding this cake, one thing became clear from this video: the recipe as printed in that pocketbook is — I knew it — missing one ingredient, evaporated milk. It makes me wonder how people could have had success replicating this cake using what is clearly a wrong recipe.

Watch the video at 3:31. Canned evaporated milk is added to the batter after sweetened condensed milk.

Mariyah stressed many times during her conversation with me that Badin cake isn’t like any other butter cake. The texture isn’t supposed to be light and fluffy. That’s why, according to her, no leavening agents are used. Nothing but a brief fermentation (if you can even call it that) is used to create a cake-like texture that’s not too dense or fluffy.

The way they do it at the bakery is to start by beating the eggs and sugar with a machine just until the sugar dissolves. The egg mixture doesn’t need to have much air incorporated into it. Then everything is mixed by hand as you can see in the video above. After the batter is well mixed, it is left to ferment for 2-3 hours then baked.

I don’t quite understand why, but that didn’t work for me at all. I tested this recipe at least 8 times and I failed every single time until I decided I needed to find my own way to recreate this cake. And I did. It involves some baking powder which has put a dent in my ego. But I don’t find the fermentation of the unleavened batter to be helpful in creating the desired texture. All it did was causing the surface of the cake to dome up unevenly in the oven and the texture to be almost as dense as almond paste.

I came up with something that’s as close to the original as I possibly could. I’m very pleased with the result, but if anyone has a way of making the same thing without any leavening agent and using the method you see in the video, I’m all ears.

My Take on Thai-Muslim Cake (Khanom Badin)

Makes one 9x12x3-inch pan or one 10-inch springform pan

Printable Version

150g (1/2 cup) sweetened condensed milk

110g (1/2 cup) whole milk

20g (2 tablespoons) plain vegetable oil

80g (~6 tablespoons) butter, softened

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

½ teaspoon salt

2 teaspoons baking powder

200g (1 ½ cups minus 1 tablespoon) all-purpose flour

5 large eggs, room temperature

200g (1 cup minus 1 tablespoon) sugar

- Grease (and, if necessary, line with a piece of parchment paper) a 10-inch springform pan or a 9x13x2-inch pan; set aside.

- In a large mixing bowl whisk together the first seven ingredients until smooth. Whisk in all-purpose flour, making sure there are no lumps. You’ll have what seems like an abnormally thick batter. Fear not; it’ll be okay.

- Preheat the oven to 350 F. Position the rack in the middle.

- In another mixing bowl, beat eggs with an electric mixer on high until they are pale and gaining volume. Add sugar to the eggs a little at a time while continuing to beat. You know the egg mixture is ready when it has tripled the original volume and taken on a pale color; when dropped from the beaters onto itself, it will also form a slow ribbon-like shape.

- At this point, the disparity between the consistency of the flour mixture and that of the egg mixture is quite great, so in order to be able to mix the two together without deflating the egg mixture is to do it in gradually. Lighten up the flour mixture a bit first by folding in 1/3 of the egg mixture. This makes folding in the remaining 2/3 easier.

- Once the batter is well blended, pour it into the prepared pan. Tap the pan against the counter top a few times to get rid of air bubbles.

- Bake the cake for 30-40 minutes or until the top is golden brown and the center passes the toothpick test; remove the cake from the oven.

- While the cake is still warm, press a few candied cherries or maraschino cherries into the top just deeply enough so that the top of the candied fruits are almost flush with the surface of the cake. Let the cake cool completely before serving or storing.

25 Responses to Khanom Badin: Thai-Muslim Butter Cake (ขนมบดิน)