What criteria do you use to gauge how much you understand another culture? How do you rank these criteria in terms of their importance? How objective is your ranking and what are the factors influencing it? What characteristics must someone from a different culture exhibit – what knowledge must they possess for you to consider them well-assimilated or at least well-versed in your culture? What are the things you need to do or say or prove in order to assure someone that you really understand their culture? What criteria do you think someone else from a culture different from yours may use to measure your understanding of their culture? I often wonder about these things.

To Jon, one of the first American friends I made when I first came to this country, the ability to match random movie quotes with the Hollywood movies from which they come ranks number one on the list of criteria which he used to measure a foreigner’s understanding of the American culture. And, according to him, I was pretty good at it.

I used movies as a way to familiarize myself with colloquial English before I came to the US; that’s how I knew those movie lines. When you watch lots of movies multiple times, you’re bound to remember some lines. But that’s pretty much the extent of it. Yet, somehow Jon formed in his own mind an erroneous belief that someone who knew lines from Cool Hand Luke, The Godfather, The Shawshank Redemption, The Princess Bride, and Forrest Gump must have also known everything else about the American culture.

I don’t know how he coped with the cognitive dissonance that came with watching me do and say things that made it clear to most people that I was not from here. I figured it must have been confusing to him.

All this made me think: Do I have some criteria with which I’ve unconsciously used to gauge someone’s understanding of the Thai culture?

I thought about it quite long and seriously. And I’ve discovered that things such as removing one’s shoes before entering a home, not pointing at things with one’s foot, greeting an older person with a wai, or not touching someone’s head, etc., rank pretty low on my extremely personal, subjective, inexplicable, indefensible, irrational, and probably unfair list of criteria.

Hovering the top of the list, on the contrary, are:

1. Familiarity with Po Intharapalit’s Phon Nikon Kim-nguan (often dubbed “Three Buddies” in English), a humorous pocket book series which I am unalterably convinced is untranslatable. To appreciate the humor — some obvious and some very subtle — one needs to understand not only the Thai language but also the history and culture of Thailand all the way to the pre-WWII era. You can walk into my house with the shoes on and speak Thai with all the tones messed up. You can point your foot in my direction while patting on my head. But if you like Three Buddies and understand the behaviors of the main characters, you’re Thai to me — we may even be related.

2. Familiarity with Thai spoonerism. Is it irrational of me to equate full assimilation into the Thai culture with the ability to detect, to produce, and to use Thai spoonerisms deftly and appropriately? Plo say nease.

3. Familiarity with Thai old superstitions and ghosts. I’m not talking about believing in those things. Heck, I certainly don’t. I’m talking about knowing — really knowing — about them. There’s no need to believe in these things or condone a belief in them. But to understand, blend into, or change a culture, one needs to be informed of some of the things that are ingrained in said culture.

4. Familiarity with a family of Thai chili relishes, nam prik (น้ำพริก), as well as how to eat and serve them.

I won’t talk about criterion #1 here, because once I start talking about my beloved Three Buddies, chances are I won’t shut up. I won’t talk about #2 either, because the subject of Thai spoonerism will inevitably lead you down the R-rated path. Let us, therefore, focus our attention on Thai ghosts and Thai chili relishes (which, as I’ll show you later, are more objective than the first two criteria).

Thai ghosts are an interesting bunch. You have the have-pestle-will-travel male ghosts (ผีกระหัง) who move around on – you guessed it – a large old-fashioned wooden pestle. Two round and flat bamboo baskets are attached to the arms and flapped to create air lift. Their female counterparts (ผีกระสือ), on the other hand, rely on no flying equipment. They live by day as human; at night their heads disconnect from their bodies at the neck and they fly around the neighborhood with just the heads and innards, looking for dirty things to eat then wiping their mouths on the clothes you hang outside to dry overnight (you can see them here, if you dare). Then we have the jungle ghost, onomatopoeically named kong-koi (ผีกองกอย) after the odd sound they make, who like to skip around on –- don’t ask — one leg looking for things to consume (mostly blood).

But none in the entire history of Thai ghosts is better known or better loved than Mae Nak Phra Khanong (“Miss Nak of Phra Khanong District”). I think if there’s one ghost that the Thai people genuinely empathize with — no, root for — it’s Mae Nak.

Here’s a quick synopsis. A young woman, Nak, was pregnant when her husband, Mak, was sent to war. Nak later died from childbirth. But wanting so much to be with her husband again, Nak’s spirit continued to live in their marital house, disguised as a human. She used her ghostly power to scare the entire neighborhood into keeping quiet about her, um, condition. Well, Mak came back from war eventually and was happy to be with Nak and their newborn baby (also a bona fide ghost) again — that is, until he started noticing unusual things about his wife. Mak’s cumulative doubts reached a crescendo one night when Nak was making a chili relish.

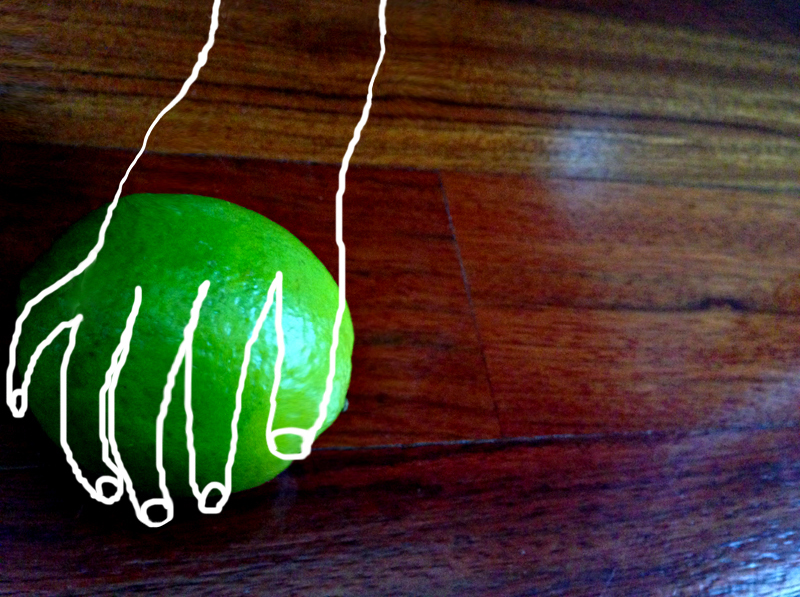

It was supposed to be just another quick, fuss-free weeknight family meal, you see. But because, apparently, ghosts are just as clumsy as some of us are, Nak dropped a lime which fell two floors to the ground. (To visualize this, you need to look at this picture which shows how a traditional Thai home is raised from the ground; basically, you live on a second floor.) You and I would have walked down to the ground floor to retrieve the lime. Not Nak. She opted for stretching one of her arms all the way down from the second floor to the ground floor to grab the wayward fruit. Because she could. Then she continued making the relish as if nothing happened.

Unbeknownst to Nak, her husband saw what happened. That’s when stuff got real. That’s when Mak knew for sure his wife wasn’t human. That’s when he came up with an escape plan. That’s when he sought help from other people who thus far had been too scared to tell him the truth. That’s when Nak got really ticked off. And that’s when, hooboy, things got really scary for the entire neighborhood.

There are several versions of the story of what happened after that (you can read more about it here). The legend of Mae Nak Phra Khanong has been turned into nearly 20 movies since the early 60s; no other Thai ghost can match Nak’s popularity. The story might have happened long time ago when Phra Khanong District seemed so far away from central Bangkok as if it were a distant city. But the legend still resonates with people who live in the era when it takes, oh, 20 minutes via skytrain from downtown Bangkok to Phra Khanong. It’s Nak’s love for her husband that has tugged at the heartstrings of the Thai people for decades. Even the latest cinematic version, Pee Mak Phra Khanong (Mr. Mak of Phra Khanong District) released early this year, which is told from the POV of Mak with all kinds of comedic elements added to it, is still very sentimental. (I really like this version. You can watch the hilarious trailer complete with English subtitle here).

At the heart of it, the legend of Mae Nak is a love story and a timeless one at that.

But since I’m the type that always misses the point, the one thing in the legend of Mae Nak that has held my interest all these years is: what kind of chili relish was Nak making when she dropped a lime?

With that we’re moving from criterion #3 to criterion #4 which happens to be very objective. Food is a major part of Thai culture, and, as any expert will tell you, pastes lie at the very heart of Thai cuisine. A paste of herbs, aromatics, and spices represents a most primitive form of Thai food. A chili relish is built upon that foundation. We’ll talk more about this in due time. For now, let’s just say that until one familiarizes oneself with dishes in the relish genre, one merely dances around the periphery of Thai cuisine.

The legend – this annoys me – does not state what kind of chili relish Nak was making. But I’ve always visualized it as shrimp paste chili relish or nam prik kapi (น้ำพริกกะปิ), a condiment (a full-fledged dish in the rice accompaniment category, if you ask me) that is never far away from the table of central Thai families including mine. Recipes for the relish vary from family to family, but its most basic form is a paste of garlic, Thai fermented shrimp paste, and fresh chilies that is seasoned with fish sauce and a sour fruit – lime, most of the time.

I grew up on this stuff, so I’m used to it. Those who are not familiar with this relish, approach it cautiously. Consult my post on how to eat a chili relish, and start by dabbing just a little of it on a bite of rice. Next time around, you may want to make a Thai omelet, top your rice with that, and dab some shrimp paste relish on each bite. Start small and slow. But do start somewhere. You don’t have to like it. But if your goal is to get to Thai food 401, you need to take this required prerequisite course. There’s no other way. If you don’t have that goal in mind, this is completely optional. There are a lot of other Thai dishes that aren’t this strong and pungent to be enjoyed.

This recipe is one of the many varieties of shrimp paste relish often served at our house when I was growing up. The original recipe calls for the rind of bitter orange (ส้มซ่า som sa) which we grew in the garden. But you can use fresh lime rind.

- 2-3 limes

- 2 tablespoons dried shrimp

- 2 large cloves garlic, peeled

- 2-3 (fewer of less depending on your taste) fresh Thai bird's eye chilies

- 2 teaspoons packed Thai shrimp paste

- 2 teaspoons packed grated palm sugar or 1 teaspoon packed light or brown sugar

- Some fish sauce (just in case; you may not need it at all)

- Zest 2 limes, being careful to avoid the white pith. Alternatively, you can peel the lime rind with a vegetable peeler or paring knife into thin strips, avoiding the white pith, then with the strips arranged into stacks of 3-4, cut crosswise into thin slices. Set the lime zest aside.

- Juice the 2 limes which you've just zested. You need 2½ tablespoons of juice. If you don't get this amount out of the 2 limes, get more from the 3rd lime.

- In a mortar or a small chopper, grind the dried shrimp, garlic, chilies, shrimp paste, and sugar until no chunks larger than a match head remain.

- Transfer the paste to a small bowl. Stir in the lime juice and zest. Taste it. If you're not used to Thai shrimp paste relish, expect the flavor to be very strong for you. Instead of tasting the relish by taking in a spoonful of it, it's best to do so by dipping a spoon into it and dabbing just the little bit that clings to the spoon on the tip of your tongue. The relish should be equally salty and sour with just a faint hint of sweetness -- at least that's how I like it.

- Serve with rice, steamed and fresh vegetable crudités, and grilled, steamed, or fried fish (prepared with as little seasoning as possible).

- The relish can be stored in a covered container in the refrigerator for 1 week or frozen for 6 months.

27 Responses to Shrimp Paste Relish with Lime Rind (น้ำพริกผิวมะนาว) and a Little Ghost Tale