Weighing down on my mind these past few weeks are questions regarding the state of Thai cuisine in the motherland. Another issue related to it involves the definition of authenticity. Does it involve a cuisine being frozen in form and canonized at some point then rote-produced thereafter? Or is cuisine, like language, a dynamic entity that changes and evolves along with the culture of which it is part? If that’s the case, could it be that authenticity is irrelevant at best and meaningless at worst. What is the definitive Thai cuisine?

Clearly, I have more questions than answers. And I am frustrated to the core by the fact that no matter how motivated I am to search for answers, the scarcity of written records always sets me back. What is wanting in the area of verifiable information is compensated for with a plethora of opinions based on oral traditions and hearsay. This is one of those times when I wish opinions weren’t a dime a dozen.

More interestingly, in the absence of substantiated theories and a corpus of definitive texts worthy of respect, the public understandably trembles in reverence before any work that takes on the outward appearance of authority. To be fair, that could also be due to a lack of better alternatives. A tinge of pain is felt as I’m writing this paragraph. What causes it, I don’t quite know.

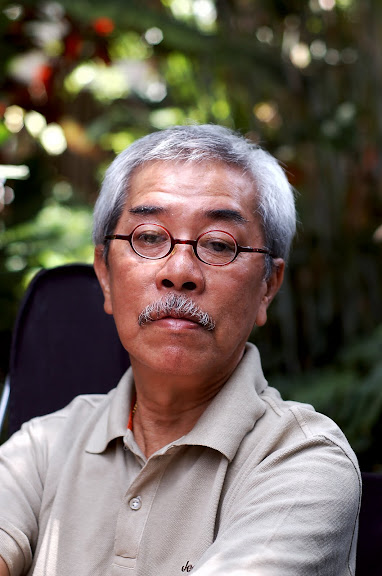

“It’s our fault,” said Suthon Sukphisit, a veteran Thai journalist/writer whose excellent works on food and travel have appeared in various publications. “We’ve been complacent when it comes to reading and acquiring knowledge.” He knows first-hand how books that are written to educate have never been received by the public with the kind of enthusiasm reserved for prime time drama or fashion magazines. The prolific author was sitting in his Bangkok-based residence full of unsold copies of his books at the time of the interview. That said, Suthon wasn’t bitter about the situation as much as he was accepting of it.

Though I had read Suthon’s food and travel columns in Thai for years, I’d never had a chance to speak with him until a few days ago. To my delight, the way my favorite writer talks in real life is exactly like how he comes across through his writing; concise, direct, free of fluff, intelligent, and witty. He knows his stuff. He is opinionated. He’s not shy to tell you what he thinks, albeit with no trace of arrogance. When he disagrees with you, he knows how to present his viewpoint respectfully and defend it intelligently as opposed to emotionally. I like these things immensely in a person.

And so we talked for a while about miscellaneous things in regards to Thai cuisine and the state of decline which it is in — allegedly. Much of what we discussed has been written by Suthon in a recent Bangkok Post article, so I won’t repeat it here.

As it turned out, many of the questions I had regarding Thai cuisine remained unanswered. In saying that we have drifted away from what authentic Thai cuisine used to be, the implication is that there’s the definitive version to return to. But what does it look like? Is it really so much better than what we have now that we should all go back to that era — whichever it is in our history — and recreate its cuisine? Having had what we’ve had and been exposed to so many other cuisines and ingredients from around the world, would we even want to retrain our palates to enjoy the cuisine created in the time when we were limited only to what we had locally?

But I was focusing on the wrong issues according to Suthon. “It’s impossible and pointless to capture the exact characteristics of the prototype of each dish,” he waved off my questions. “The only written records available to you date back no earlier than the time the printing press was first introduced.” Suthon was referring, of course, to the mid-1800s** which is the beginning of the era of written records that can shed light on the history of Thai cuisine in any meaningful way. And even though some dishes that are still enjoyed today date back to the 16th century, pertinent information before mid-1800s is scarce and not entirely reliable.

What I should have focused on, said Suthon, was how the Thai composed their dishes and the social milieu from which the dishes emerged. Cuisine, culture, and society intertwine; you can’t understand one without learning about the others. Traditional Thai cuisine was very simple, according to Suthon. It comprised ingredients that were available within one’s immediate surroundings and was devised based on common sense. “Take green curry for example,” Suthon began a topic which would prove to be quite revelatory to me. “The paste was originally designed to be used with low quality cuts of beef.”

Being tough and sinewy, the meat needed to be slowly simmered for a long time. To cover up the gaminess, larger amounts of coriander and cumin as well as fresh green chillies were used in the curry paste. And so this was the beginning of how we got green curry which was different from red curry. “A lot of thought went into devising a dish,” said Suthon. “People didn’t throw herbs and spices together willy-nilly.” Without knowing how green curry came to be or the purpose behind it, people have deviated from the original composition over time and come up with what they think are clever adaptations. “You see all sorts of green curries,” Suthon said. You could detect mild weariness in his voice. “Green curry with shrimp balls (oops …), green curry with fish, green curry with chicken, dry green curry, …” Suthon stopped himself just in time before he turned into the beloved Bubba of Forrest Gump fame.

Is there no room for creativity and different interpretations? I had to ask him that. After all, we can all agree that cuisine exists to serve us and not the other way around. What if I don’t like beef in my green curry? What if I want to flavor Tom Yam with vinegar instead of lime juice? (I don’t, but you know …) “Oh, yes, there is!” Suthon didn’t miss a beat. The solution to that is very simple, he said. “Just call the dish by a different name.”

He blamed street vendors and restaurateurs. Competition, Suthon theorized, has forced people in the food business to constantly come up with creative spins on the traditional dishes. The need to widen the profit margin has also driven many to replace traditional ingredients with cheap, inferior substitutes. The media has also failed us, lamented Suthon. “Most food shows are about where to eat and what to eat,” Suthon echoed what he had said before in various places, “They’re presented by movie stars or comedians who have appeal to the masses but no real understanding of the food or the history behind it.”

I think what troubles Suthon as someone who has devoted his life acquiring and sharing knowledge of the history and culture of Thailand is not the evolution of Thai cuisine. In other words, he doesn’t lock himself up in his home refusing to eat anything perceived to be a bastardized version of what it once was half a century ago. His concern is over the fact that we have lost an understanding of the roots of our cuisine and culture. The perceived complacency and disinterest in remedying that only make the picture more grim.

I guess it’s like saying that even though there’s no expectation that people would go back to speaking the language and employing the vocabulary of the last century; there is expectation that we know something about etymology — the roots of the words in our current vernacular.

It would take at least a dozen PhD dissertations to fully explain the perceived lack of knowledge and interest to learn about Thai cuisine among the Thai. Not everyone is complacent or uninformed, of course. Surely there are some who seek to learn but know not where to find solid information. Suthon himself has never been trained professionally in culinary arts or food history either; he’s just been an avid reader. Spending a good part of his youth helping out his mother in the kitchen also got him acquainted with traditional Thai cuisine.

I’m fortunate in that regards, I guess. I don’t consider myself an expert in Thai cuisine, or any cuisine for that matter. However, what I do have which can never be taken away is the privilege of growing up in a home with an extensive library and being around my grandparents who insisted I learn how to make Thai food from scratch, how to grate coconut the old-fashioned way, etc. I was constantly regaled with stories of how things were done during the times my grandparents were children. I didn’t see much value in those things when I was younger, but like it or not they have stuck with me. And though I still don’t know as much as I hope I do, my curiosity knows no end. In fact, it hurts me sometimes.

What has frustrated me is the lack of information. Take the dish featured here, for example. I asked Suthon to think up a dish to be featured in this blog post, and, after disappearing for a couple of days, he got back to me with Ma Haw,*** a retro appetizer that is uniquely Thai. According to Suthon, Ma Haw entered the culinary scene in Thailand sometime within the last century. A well-staffed kitchen of one of the affluent nobles and aristocrats was most likely its birthplace. “These homes saw many visitors at various times each day,” said the history whiz. “You need to have something on hand to serve to the guests.”

Ground pork (some use ground pork and ground shrimp) is sauteed with a paste of cilantro roots, garlic, and white peppercorns, along with some shallots, and heavily seasoned with palm sugar and fish sauce. Once the paste is getting thick, finely-chopped toasted peanuts is added to the mixture. The end result is a thick, sticky mass of goodness that gets shaped into tiny spheres and placed on top of pieces of tart pineapple or orange. Fresh cilantro leaves and thin slivers of fresh red pepper finish it off. The sweetness and nuttiness of the pork-peanut mixture perfectly complement the tartness of the fruit. Each bite offers various flavors and textures that are perfectly combined.

What neither Suthon nor I could figure out is how the name Ma Haw came to be. A lot of people interpret it as “galloping horse.” And they may be right. That interpretation, however, is based solely on the spelling variant, “ม้าห้อ,” assuming that it is the only legitimate way the name is written. If that was true, this paragraph would have been unnecessary. The truth is that there are two more spelling variants in circulation: ม้าฮ่อ and ม้าห่อ. The first of the two, ม้าฮ่อ, is a perfect homophone of the most common spelling variant, ม้าห้อ. But while one refers to a galloping horse, one refers to a horse of Yunnanese (ฮ่อ) origin. It doesn’t make much sense, I know. But then again, the “galloping horse” option doesn’t make all that much sense either. As for the third variant, ม้าห่อ, which has a slightly different tone, I am at a loss as to what the heck it refers to.

In short, something equestrian is involved; we don’t know much else. Hence my complaint about the lack of written records.

I can easily find out exactly how the ancient inhabitants of Sumer brewed their beer even though that happened nearly 4 millennia ago (thankfully recorded in a highly durable form of document). On the contrary, I can’t find one piece of credible evidence detailing how and via whom massaman curry came to be assimilated into the Thai cuisine. Theories abound; solid proof is nil. And we’re talking no more than 5-6 centuries ago.

I guess I’ll never know how a ball of sweet porky, peanut-y paste and a piece of fruit form an appetizer oddly named “galloping horse.”

Ma Haw

(serves 6 as an appetizer)

Printable Version

1/4 lb ground pork

1/4 lb ground shrimp meat

(You can also use 1/2 lb ground pork and forget the shrimp)

2 cilantro roots or 3 tablespoons finely-chopped cilantro stems

2 cloves garlic, peeled

1 teaspoon whole white peppercorns

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

2 medium-sized shallots, peeled and thinly sliced

1/3 cup coarsely-ground roasted peanuts

fish sauce

palm sugar

one pineapple, trimmed, cored, and cut into 1/2-inch thick bite-sized pieces

fresh cilantro leaves and red pepper cut into thin slivers, for garnish

Note: The pork mixture can be frozen and thawed for later use, but it’s imperative that you assemble this appetizer no longer than half an hour before serving time. The pork mixture tends to draw out excessive juice from the fruit when they are in contact for too long.

*The fact that most, if not all, documents up to the end of the Ayutthaya were destroyed when the city was sacked in 1767 doesn’t help.

**Pieces of history have been preserved in written form in various genres one of which is funerary literature. It needs to be said that the primary purpose of those books is to commemorate the life of the deceased and the primary audience consists of family members, close friends, colleagues, and acquaintances of the deceased who attend the cremation ceremony where copies of these funeral books are traditionally distributed.

They are meant to serve as a gift or a souvenir to those who know the deceased personally; not to be used for commercial gain. Grievously for some of us and conveniently for others, many of these books, including — I’m sure — ones distributed at the cremation services of my loved ones who have passed on, can be purchased from various used bookstores. Many of these books are so old that they’re no longer protected by the copyright law and can, therefore, be legally reprinted/repackaged without permission or regards to the original intention of the deceased or the families. Anyone who desires to learn about the Thai culture in the last century or so can access many of these funeral books in the archives of a temple in Bangkok, a place to which the relatives of the deceased intentionally donate a copy for the edification of the Thai people with no expectation of financial gain.

Sadly, it seems this concept of vidyadana or วิทยาทาน (from Sanskrit vidyā विद्या “knowledge” and dāna दान “generosity/giving”) is perhaps not universally understood.

***Also spelled Ma Hor or, if you want to play by the rules, Ma Ho.

12 Responses to Ma Haw (ม้าห้อหรือม้าฮ่อ) and the State of Thai Cuisine: An Interview with Suthon Sukphisit