If those who follow me on Twitter have wondered why it took me so long to finally publish this post on Thai Sour Curry or Kaeng Som (แกงส้ม) after I’d announced it nearly two months ago, check out the length of this post. There’s so much to say about this curry, so many possible angles from which to approach the subject. When you see how much information I’ve been forced to relegate to the footnotes to keep the length of this post reasonable – and it looks like I’ve failed miserably – you’ll understand the procrastination.

After all, it’s kaeng som[1], one of the grande dames of Thai curries, we’re talking about. It’s the curry that captures so very well the flavors associated with traditional Thai food. A short, quick post would be disrespectful.

We loved kaeng som in our family. We loved it so much that it was served at least twice a week, or more if you count the leftover meals. And on the days when I didn’t have kaeng som at home, it would be served at school. If Brillat-Savarin is right, then I am nothing but a big bowl of kaeng som.

Opinions on Kaeng Som

You can’t love truly unless you love passionately.

I totally made that cheeseball line up. But didn’t D. H. Lawrence say something about how if you’re moved by passion, then you say something and say it hot — or something like that? Well, when it comes to Thai sour curry, which is – no polls are needed to verify this – a national favorite across all regions and socio-economic strata, everyone[2] seems to want to say something and say it hot.

Years ago, I came across a magazine interview of one of Thailand’s most celebrated senior actors, Sorapong Chatree, in which he, a native Ayutthayan, expressed disgust over the type of anemic, thin-as-water kaeng som he often found at inferior eateries throughout Bangkok. His mother’s version, said the actor, was always thick, rich, and full of flavor. And even though I remember neither the name of the magazine nor the exact time it was published, that comment has stayed with me, because it’s the exact same comment everyone in my own family makes every single time we go out to eat and get served this type of thin, watery kaeng som.

When this happens, you wonder if the cook makes it that way because he or she doesn’t know better or simply due to carelessness and greed for profit while hoping the diners won’t know better.

“Disgusting,” I can still hear my Uncle S (known for being a food snob as mentioned in my post on Thai lime-chilli-garlic steamed fish) say under his breath whenever we walked by a street food stall selling this kind of watery kaeng som. “You can see from across the street. The broth is as thin as the water I use to wash these.” He pointed at his feet. (Uncle S is not known for mincing words.)

Polsri Kachacheewa, director of The Modern Woman Cooking School in Bangkok whom I highly respect, also made this comment to me when we talked recently. “These days, all you see is kaeng som with deep-fried whole fish,” said Polsri of one of the most prominent restaurant versions of kaeng som. “There was no such thing years ago!”

The frying of the fish, he theorized, most likely originated as a clever way of masking the lack of freshness of the fish. “What else can restaurants do with fresh-water fish that’s old and smelly,” said the Thai food guru. “They fry it, of course.”

Then the trend caught on.

Suthon Sukphisit, a well-respected food and travel columnist in Thailand, said when I asked him about kaeng som, “This is the curry that fells giants.”

That’s his way of saying that those approaching this curry with a haughty attitude, thinking it’s child’s play, have often been put to shame. True, the curry is dead easy to make – just a matter of dissolving a paste into water. But to make it well? That’s an entirely different story. The consistency has to be right; the flavor balance has to be right. With such a short list of simple ingredients, any shortcoming would be very noticeable.

He also has something to say about a variation of kaeng som which has now become mainstream, kaeng som with cha-om cakes.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if this started out as a way of getting rid of old nam prik sides,” he said, referring to eggy cakes of acacia pennata, a quintessential accompaniment to the Thai shrimp paste relish, nam prik kapi. “Then it became a runaway hit.”

Most street food stalls always have kaeng som and nam prik kapi as the main staples, and Suthon opines that it’s natural for the relishes to run out more quickly than the vegetable sides and for the vendor to dump those leftovers into a very forgiving, accommodating, any-vegetable-goes curry like kaeng som.

It could be true, as some have claimed, that this variation of kaeng som is an ancient recipe which was once forgotten then recently revived. But all I know is that my experience has been the same as Suthon’s; I hadn’t seen kaeng som with cha-om cakes either — until recent years.

But Suthon is not making a big deal out of how this variation came about; food constantly evolves, after all. And in this case – you’ve got to admit – it evolves in the right direction. Kaeng som with cha-om cakes tastes pretty darn good and has unsurprisingly become a favorite among both Bangkokians and patrons of Thai restaurants in the US (following the proliferation of Thai restaurant secret menus in the US). Besides, Suthon himself always insists that kaeng som and khai jiao (Thai-style omelet) are made for each other.

I wholeheartedly agree.

And then we have my nanny, Auntie T, who was also our cook.

Although Auntie T doesn’t have a strong opinion about other people’s versions of kaeng som (or anything else, for that matter), she has over the years stuck with one and only one way of making kaeng som, alternating between two and only two vegetables, namely green papaya and Thai water morning glory. This is not due to the lack of imagination or unavailability of other ingredients; she just thought those two were the best among many vegetables which one can use in kaeng som. Also, she doesn’t believe in using shrimp meat in the paste either for that results in “a wimpy broth.”

I guess that’s a strong statement in itself, and now that I think about it, she’s quite opinionated.

Kaeng Som-Compatible Vegetables

Kaeng som is a great vehicle in which home-grown vegetables are served. Ask people who come from traditional Central Thai households what vegetable represents the most prevalent kaeng som ingredient to them and, most of the time, they would refer to the fruits, leaves, and blossoms from the plants grown within the fences of their home.

Ask my cousins, and they will say it’s either moringa pods (ma-rum) or Sesbania grandiflora flowers (dok khae) for those grew in their home. Ask those who only get to eat kaeng som at family restaurants and they’ll say it’s either a mélange of different vegetables or water mimosa (phak kra chet) for those are used quite heavily at restaurants.

Ask me and I’d say it’s green papaya for, you see, we had a very fertile papaya tree right outside the kitchen window.

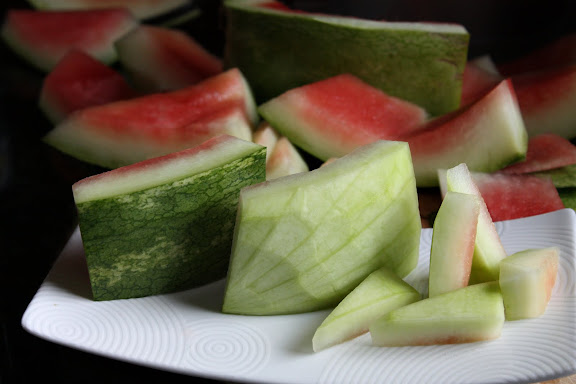

But these are just a few examples; there are many more vegetables and fruits that can be added to the very accommodating kaeng som. All kinds of summer squash work well. Watermelon rinds stand out as a favorite of mine. Chayote has also become a new favorite. Chunks of cauliflower, green beans, and daikon also mesh well together in kaeng som. During the advanced years of her life, my maternal grandmother loved the soft napa cabbage in her kaeng som. My mother, on the other hand, wouldn’t eat any kaeng som unless it had Thai water morning glory in it.

The only few vegetables I wouldn’t use include – though are not limited to – eggplants, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, starchy root vegetables, and green leafy vegetables, such as collard greens. But other than those you can use anything or mix and match all you like. When multiple vegetables are used, you just have to be mindful of how long it takes to cook each one of them. Different vegetables cook at different rates, even though they’re cut into the same size. Therefore, be sure to always add those that take the longest to cook first, followed by those that take less time to cook.

Auntie T’s Kaeng Som

It’s impossible to identify one version of kaeng som as definitive, because each region has its own. The South has its own kaeng som[3]; so does the North and Northeastern. And the type of kaeng som featured here can only be described as being most consistent with what you’ll normally see in the Central Plains. A true blue Bangkokian, I grew up eating this version of kaeng som; it’s the only version my Auntie T ever made for us.

Recipes, of course, vary even within the central part, though not by much. However, in general it’s safe to say that central kaeng som is soured with prepared tamarind pulp, thickened with cooked fresh-water fish flakes that have been added to the curry paste, and does not contain turmeric or coconut/palm vinegar (sometimes lime juice) as is the case with the southern version.

Auntie T’s kaeng som is made with the simplest of paste ingredients: dried red chilies, shallots, and shrimp paste. While preparing the curry paste, Auntie T would poach a gutted snake-head fish (pla chon) whole. She would then scrape the cooked fish meat off its bones, discard the skins, and throw the bones and the head back into the same pot in which she’s poached the fish. She’d let the liquid simmer some more to extract as much flavor out of the fish bones as possible. The resulting fish stock, with all the fish junk strained out, would eventually be used in the curry base.

The cooked meat would then be pounded into the curry paste which would be dissolved into the boiling fish stock. Then the vegetable would go in, followed very closely by fish sauce, tamarind pulp, and palm sugar to taste. Once the desired taste is achieved and the vegetable is cooked through, the curry is done.

Commercial Kaeng Som Paste

Living in an area where a mere sighting of fresh kaffir lime leaves is enough to cause the most emotionless of Thai food-loving adults to burst into joyous sobs, I know how difficult it is to find every single fresh ingredient necessary to make traditional Thai curry pastes, i.e. ones that don’t foolishly contain ginger when wild ginger is called for or lemon zest when lemongrass is required. And if you’ve followed this site for a while, you know I don’t ever look down on those who use commercial curry pastes. (More on this in my post on Easy Thai Green Curry.)

However, with kaeng som, I’d like to encourage you – if I may – to try making the paste from scratch. First of all, all of the ingredients are easy to find. Secondly, it’s very easy to make. Thirdly, it’s one of those pastes that still taste wonderful even when done in a food processor. Lastly, most commercial kaeng som curry pastes, in my opinion, don’t taste that great. My apologies to all the brands out there, but it seems while they’ve done a great job with other kinds of curry paste, that doesn’t seem to be the case with their kaeng som paste.

Try spending a couple of hours making a gallon’s worth of kaeng som base to use in the weeks that follow. (I always do that, because I live a busy life as well and don’t always have time to make things from scratch every time I have a craving for them.) Season it until it tastes great to you, then divide the curry base into smaller containers, and freeze it for later use. Then all you have to do is reheat the base, add whatever vegetable(s) you have on hand, and your kaeng som is done in less than 15 minutes. Sometimes, I add some shrimp to it (or sometimes a catfish steak as shown) just before the vegetables are done; most of the time I don’t for there’s already plenty of fish meat in the curry base.

But if anyone wants to start with commercial kaeng som paste just to see how it is, they’d be wise to pay attention to the ingredient list and cooking instructions on the package. Some brands include the fish meat in the paste in which case all you have to do is dissolve the paste into the stock or water; some brands don’t include the fish meat in which case you need to blend in some cooked fish meat before using it. Also, the ones that include fish meat always come pre-seasoned, so proceed accordingly.

- 10 grams dried red chilies (I use arbol), soaked whole in hot water until soft then drained well

- 60 grams of peeled shallots, sliced thinly

- 20 grams Thai shrimp paste

- 1 teaspoon of salt

- 250 grams skinless, boneless meat of poached trout or catfish

- 6 cups of plain fish stock (made of nothing else but fish bones and water)

- 134 grams (1/2 cup) prepared tamarind pulp

- 4 tablespoons fish sauce

- 30 grams palm sugar

- In a granite mortar, pound the chilies and salt together until you have a smooth paste with no visible pepper seeds.

- Add the shrimp paste and continue to pound until smooth.

- Add the sliced shallots, a couple of tablespoons at a time, and pound until smooth.

- Add the fish meat and pound until you have a smooth paste.

- Put the fish stock in a pot and bring it to a gentle boil.

- Stir in the prepared paste, followed by tamarind pulp, fish sauce, and palm sugar.

- Once the palm sugar completely dissolves, taste and correct the seasoning as necessary. The flavor should be predominantly sour, then salty, and a little sweet.

- Your kaeng som curry base is now ready to be used right away or frozen.

- To assemble a 2-serving portion of kaeng som, bring 2 cups of the curry base to a boil in a medium pot, add desired vegetables. Once the vegetables are almost ready, add cubes of fish fillets or peeled and deveined shrimp and gently cook until the fish or shrimp is done.

[1] Kaeng Som literally means sour curry, i.e. curry characterized by the sour flavor.

I cringe whenever I see kaeng som referred to as “Thai sour orange curry” or “Thai orange curry.” I really can’t think of any good explanation for why the word “orange” is needed there. The only thing I can think of is that the “orange” part might be an attempt – a misguided one – to account for the Thai word, “som” (ส้ม), which is generally used to refer to orange the fruit and orange the color in the Thai language.

To take this as a reference to som the fruit – as if to suggest that orange is one of the ingredients – is ludicrous for even those who don’t cook know that kaeng som contains as much orange as Grape-Nuts contains grape. Could it refer to orange/som the color? That makes no sense for this curry has the exact same color as the so-called red curry, and there’s no reason why one is called “red” and the other “orange.” Besides, panaeng curry and a whole host of others, which derive their reddish color from red chilies, also have the same color as kaeng som. We don’t go and stick the word “orange” in the English designations for those other curries, do we?

So it’s great that I’ve found out Thai food teacher Kasma Loha-unchit backs me up on this. The conclusion which she and I have arrived is that this is most likely a case of failure to understand the Thai language at the basic level.

You see, in addition to orange the fruit and orange the color, the word “som” also means “sour.” Granted, it is no longer used in that sense so much in the modern times (at least in central Thai) and what we still see now is mostly the remnants from the old days which have been preserved in frozen terms. But it doesn’t change the fact that “som” means “sour,” especially in the context of kaeng som.

A word doesn’t mean everything it can mean every time it is used; context determines usage. And in this context, it’s beyond crystal clear that “som” cannot refer to orange the color or orange the fruit.

Kasma has cited a few examples of other things that contain the word “som” that have nothing to do with orange but everything to do with sourness: (nam) som makham piak (tamarind pulp for cooking), Som Tam, soured pork (naem) which is referred to as mu som or jin som in northeastern and northern dialects respectively, nam som sai chu (vinegar), pla som (soured fish), etc.

The following is also something I’ve gleaned from my own study which provides additional support to what Kasma has pointed out.

The use of the word “som” to refer to sourness is found even in antiquity.

In the well-known Ramkhamhaeng Stele, popularly dated to the early 1200s (and therefore represents one of the oldest extant written historical records), a phrase is found: “… กูได้หมากส้มหมากหวาน อันใดกินอร่อยกินดี กูเอามาแก่พ่อกู …” which is translated, “… when I have obtained any sour/acidic or sweet fruits that were delicious and good to eat, I brought them to my father …”)

The underlined portion reads, “mak som mak wan,” referring to acidic (sour) fruits and sweet fruits. These two juxtaposed poles form a merismic pair to denote all fruits: the sour ones, the sweet ones, and all the other ones in between. And it would be absurd to understand “som” here as strictly referring to citrus fruits or oranges. Even more absurd would be to suggest that the first part refers to fruits with orange color.

Those familiar with the content of this inscription knows that it, especially the first part, is rife with merismic pairs. The well-known and oft-quoted phrase nai nam mi pla nai na mi khao (ในน้ำมีปลา ในนามีข้าว “ … there is fish in the water and rice in the fields …”), which is another clear-cut example of merism to denote how the kingdom was abundant in all things (in other words, we have more than rice and fish), also comes from the Ramkhamhaeng Stele.

For those interested in reading the English translation of the stele, go here. But for the purpose at hand, suffice it to say that calling kaeng som an orange sour curry is, to put it mildly, inadvisable.

[2] Well, everyone except Thai restaurants outside the kingdom, that is. Kaeng som is one of not many dishes that are ubiquitous in the truest sense of the word in the motherland; it’s routinely made at home, commonly found at street food stalls, and almost always served at any sit-down restaurants specializing in traditional Thai dishes. Yet, interestingly enough, Thai sour curry is found on the menus of Thai restaurants overseas not nearly as commonly as the other curries.

The question is: which comes first? Do non-Thais not know about and appreciate kaeng som, because their local Thai restaurants don’t serve it? Or could it be that Thai restaurants have tried in the past to introduce this dish, but a lukewarm response has forced them to pull it off the menu? Regardless, I hope that will change soon.

[3] What’s funny about Southern kaeng som is that the Centralites, in order to prevent confusion, have taken the liberty of assigning the name, “Kaeng Lueang” (แกงเหลือง – literally “yellow curry” which is not the same as the so-called yellow curry found on the menus of Thai restaurants in the US. But that’s for a different time and a different post) to this slightly-different version of sour curry due to the yellow hue of the turmeric. Yet, ask any Southerners who are still connected to their roots what they call the curry which Centralites refer as “kaeng lueang,” and they’ll tell you that it has been and will always be “kaeng som” to them. This, incidentally, provides further support for “som” meaning “sour” and having absolutely nothing to do with the color.

31 Responses to Thai Sour Curry (Kaeng Som – แกงส้ม)