Cleaver-flattened pieces of chicken come with your KMG in Thailand.

No reason why you can’t have big, juicy pieces of chicken like this!Khao Man Gai, one of the most common street foods in Thailand, is, in short,

a mutation, albeit controlled, of Hainanese chicken and rice. Overshadowed by the original dish and rarely included on the menus of most Thai restaurants in the West,

Khao Man Gai (RTGS:

khao man kai ข้าวมันไก่) is not widely known outside of Thailand. For us, however, this is a national favorite. In fact, just the mere mention of the name could cause collective panting in greedy anticipation.

And the reason is simple — it tastes good. How can you say no to slices of juicy and tender capon meat served with fragrant rice cooked in rich broth and a unique piquant sauce of ginger, garlic, chillies, and soy? As much as I adore the Hainanese version, it just so happens that I had already fallen in love with the Thai version before I discovered the original. I like the more spicy sauce offered by the Thai version as it balances out the richness of the chicken and the rice better, in my opinion.

From my description of this dish as a mutation, you can probably tell that it is not exactly identical to Hainanese chicken and rice. Then again, it should be noted that Khao Man Gai should not be regarded as a failed attempt to replicate the original and, therefore, inferior. The dish has become an almost entirely new entity — a delicacy in its own right. In fact, although most Thai people intellectually know that the dish is inspired by a Hainanese dish, I think we have come to think of this version as our own.

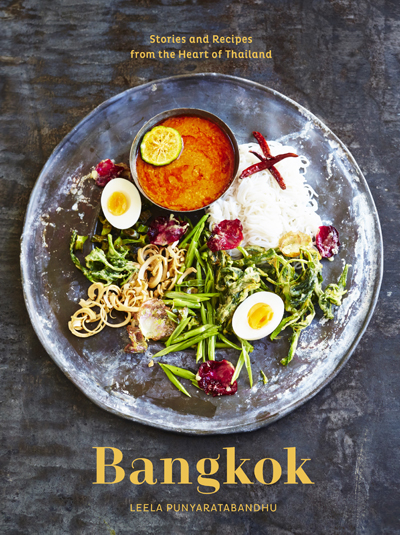

What amuses me about Khao Man Gai is how its appearance is the same regardless of where you find it in Thailand. It’s as if there’s a universal code governing the manner in which the dish is to be presented which all Khao Man Gai vendors nationwide abide by. Slices of steamed or boiled capon meat are placed over a mound of rice. Cucumber slices and fresh cilantro leaves serve as a quintessential garnish. Sometimes, a few slices of cooked congealed chicken blood (it’s not that bad …) is also added to the mix. The chicken-rice plate is then accompanied by a bowl of piping hot chicken consommé with a few pieces of Chinese winter gourd (whose Thai name is pronounced exactly like the way this little girl pronounces “frog“) swimming in it. The broth, to be slurped between bites, helps move the chicken and rice along your esophagus more smoothly.

I was actually salivating like a hyena while typing the previous paragraph. Dignity is overrated.

_________________________________________

PRODUCTS THAT HELP YOU CREATE THIS RECIPE

This is an easy recipe for home cooks. For a somewhat more involved recipe and techniques employed by the pros at a restaurant in Bangkok I went to from childhood to 2012, see Bangkok cookbook.

Khao Man Gai (or Khao Mun Gai) Recipe

(Serves 6)

Printable Version

[Check out vegan Khao Man Gai Tofu by Neven Mrgan of Panic Blog]

[Added 5-8-12: Hey, whaddayaknow, Neven is at it again. Check out how he’s incorporated Khao Man Gai sauce into a Khao Man Gai burger.]

First prepare the chicken: Place one large capon or roaster in a big stockpot and add water just until it barely covers the bird. Add a tablespoon of salt to the water and bring the whole thing to a boil. Once the water starts boiling, lower the heat and let it simmer on low, covered, until the chicken thighs move easily — a sign that the entire bird is thoroughly cooked. (You don’t want to cook the chicken beyond this point. The meat should have firm, bouncy texture, not be falling-off-the-bone tender like stewed chicken.)

Place a large bowl in the kitchen sink and fill it with iced water. This is to keep the residual heat from further cooking the chicken as it cools down. The iced water bath helps keep the chicken meat moist, firm, and juicy. Gently remove the chicken from the pot, shake off the liquid inside the cavity, and dunk the chicken into the iced water. Leave the chicken in the iced water until the entire bird has cooled down to room temperature. Remove the chicken from the water, pat it dry with paper towel, carve it, and set it aside. Keep the chicken on a covered platter.

Then make the rice: Rinse 2 cups long grain rice until the water runs clear and drain. Skim the fat off the surface of the liquid in which the chicken is cooked into a measuring cup; add enough water to the measuring cup to make a total of 3 3/4 cups of liquid. Make sure the water is very cold so that when it’s added to the fatty broth, the mixture is at room temperature which is ideal for making rice.

Stir in a teaspoon of salt (or a couple of teaspoons of soy sauce if you like your rice darker in color) Add the chicken fat-water mixture to the rice. (Don’t be scared of the fat; this is, in fact, the “man” in Khao Man Gai and what gives the rice such great flavor.) A piece of fresh ginger, a smashed clove of garlic, a bruised cilantro root, or a few white peppercorns can be added for extra flavor, but if you don’t have these things, don’t worry about it.

Cook the rice however you’d like: on the stove top, in the microwave, or — the best and the easiest way — in an electric rice cooker.

Make the sauce: In the meantime, put about 1/3 cup of roughly chopped fresh ginger (the more fibrous, the better, in this case!) into a food processor along with 4 medium cloves garlic (peeled), 5-8 red or green bird’s eye chillies (the number depends on your heat tolerance), and 1/2 cup fermented soybean sauce, 1/2 cup sugar, 1/4 cup dark sweet soy sauce, 1/4 “white” of thin soy sauce (information about dark sweet soy sauce and “white” (thin) soy sauce can be found in my post on soy sauces used in modern Thai cooking), and 1/3 cup white vinegar (not rice — oh gawd, not rice vinegar); pulse everything into a coarse puree. Pour the sauce mixture into a small saucepan and bring to a gentle boil and remove from heat after 30-40 seconds. Let the sauce cool down and adjust the seasonings as needed. In my opinion, the sauce should be primarily salty and sweet with a bit of sour taste from the vinegar. (You can make 3-4 times the amount of sauce and freeze it to use later. The sauce freezes beautifully and thaws easily.)

For the winter gourd soup: Peel and deseed approximately 2 pounds’ worth of Chinese winter gourd (daikon or chayote can also be used). Cut the gourd into 2″ x 2″ pieces. Place the gourd pieces in the liquid in which the chicken is cooked. (After the fat has been skimmed off, the remaining liquid should be quite clear.) Bring it all to a boil, lower the heat, cover the pot, and simmer for 7-8 minutes, or until the gourd is tender but not mushy. Season the broth with salt or fish sauce (soy sauce will darken the broth too much.)

To serve: Put a mound of rice on a plate and top with chicken pieces. The rice should be warm and the chicken at room temperature. The sauce can go in a small dipping sauce bowl on the side or be drizzled on top of the chicken. The necessary garnish includes fresh cucumber slices and cilantro leaves. (You can be creative with the way you plate your Khao Man Gai, but the Khao Man Gai police may be knocking on your door.)

Serve the gourd soup piping hot in a separate small serving bowl. A light sprinkle of ground white pepper is not mandatory but highly recommended.

N.B. – This is not traditional, but several Khao Man Gai vendors have offered the option of substituting boiled/steamed chicken with fried chicken. If you’re interested, here’s a recipe for Thai-style fried chicken. You can use the same dipping sauce for the fried chicken version, or you can use it in addition to Thai sweet chilli sauce.