For a country that takes such great pride in its cuisine, Thailand, surprisingly, hasn’t seemed very enthusiastic about spotlighting its food in its cinematic endeavors. If it’s true that art imitates life, then it’s quite perplexing how the magnitude of the love the Thai people have for their food and the enormity of the role food plays in their lives—all obvious to even the most casual observers—haven’t really manifested themselves on silver screen and television. And the few times when food and eating were incorporated into films and dramas, it was rarely done with any perceptible sense of intentionality.

I believe we can do better.

Then again, things have already become somewhat better than they once were. When I was growing up, scenes in TV dramas involving eating out often had the female lead character (nang ek)—soft-spoken and demure—ordering nothing more than a glass of orange juice, the beverage that had come to represent class and the ladylike gustatory restraint expected of a virtuous nang ek. This happened so much that orange juice had earned a nickname “nam nang ek,” loosely translated as “the female lead character’s beverage of choice.” In most films and TV dramas, the only people shown as taking any pleasure in eating food were the supporting characters. But then these characters would often be depicted as nerdy, gluttonous, and overweight. These caricatured characters served as comical, aesthetically-compromised sidekicks to the thin, impossibly beautiful, orange juice-drinking lead characters.

As for cooking, most characters back then, especially the female, were—with only a handful of exceptions—always portrayed as unable to cook. There is nothing wrong with not being able to cook, but this was often meant to be an indicator of the fact that she came from an upper or an upper-middle class family in which the “lowly” task of cooking would be relegated to the domestic help. Our khun nu (little lady from a rich family) had never learned to cook, because she never had to. When she attempted to fry an egg, she winced and shrieked and jumped when the oil splattered only to burn that egg in the end. The male lead character looked at her and saw how she was oh so cute—a woman of high class and someone delicate and innocent to take care of. The nang ek looked even prettier and classier with her homely, chubby, constantly-eating friends in the background.

The message wasn’t even subliminal.

But that was decades ago. The early aughts ushered in the age of foodies. Food blogs. Online restaurant reviews. Online food product reviews. The slow food movement. The DIY culture. Then came the sharing of food and restaurant visits on social media. The YUM! The OM NOM NOM. The OMG WANT! Food became cool. Eating became cool. Cooking became cool. People who made food became cool. Even young people from rich families—the hi-so, as we call it—no longer think of cooking as a lowly task reserved for their khon chai (domestic help). In fact, many of the young hi-so had started artisanal food products (with package designs straight out of Pinterest), coffee shops, and restaurants in recent years. The enjoyment of food had also become something to announce to the world. Gone were the food-averse nang ek and all the orange juice they drank.

Yet, even in the thick of the foodie era, food, food preparation, and food traditions still weren’t featured on screen with any degree of prominence in Thailand. I can think of only a couple of fairly recent TV dramas where food preparation made it into a few scenes, but that’s about it.

When Dae Jang Geum, a South Korean TV series about an orphan girl who became a palace cook and eventually a royal physician, was released in Thailand in the early 2000s, it was a smash hit, and pretty much every pair of Thai eyeballs was glued to a TV set the whole time the series was on air.

This is a drama series where food takes center stage and the Korean culinary tradition is portrayed with such reverence and such pride. The cutting, slicing, chopping, boiling, steaming are captured with such exquisite cinematography. Ingredients are also treated with such respect. The characters clearly demonstrate their love for food and eating, but in a solemn way. They’re not portrayed as gluttons but gourmands and connoisseurs. This is inspiring.

It’s probably unfair of me to use Dae Jang Geum as an example, because how can food not take center stage when it’s part of a story about someone whose job is to, well, cook? But even in other TV series where food isn’t the focus, it seems South Korean producers have managed to incorporate cooking scenes into the story so seamlessly and so well, like these scene where Ok Taecyeon cooks and packs a beautiful lunch.

Here’s the thing: I believe the Thai film and television industry has the ability to make a movie or a drama series that is just as good where Thai food is portrayed with that kind of artistic intentionality. After all, Thai food—call me biased—is second to none in the world in its beauty, its variety, and its taste. Isn’t it about time a movie or TV series like this got made?

But it’s encouraging to see while a movie or TV series that really spotlights the Thai culinary tradition is still in the future, we’re already seeing a small step in that direction. (I hope there’s more to come. We can do it, Thailand!)

If you live in Thailand, it’s nearly impossible that you don’t know this: the entire population of the country—or what seems like it—have put everything in their lives on hold every Wednesday and Thursday night ever since the drama series Bup-phe-san-niwat, entitled in English as Love Destiny, started airing a few weeks ago.

Being on the opposite side of the globe currently, I was a little late to the party. I learned of Love Destiny’s existence only recently after noticing how the Thailand-based people in the group chats I’m in had started talking in inside jokes in archaic Thai (which probably sounds like how people spoke English back in the Elizabethan era). The ones among them I’m either close friends with or related to had also been unusually slow in responding to my emails or texts. This went on for days until I came to understand why. All of these people have pretty much mentally packed up and moved to 17th century Siam, the era in which the popular drama series is set, leaving me out in the cold—alone with the worst case of FOMO.

Long story short, I, too, am watching the series along with my compatriots; I, too, am having an inbox full of unread emails; and I, too, have been accidentally slipping a few archaic Thai words into everyday conversations.

What makes Love Destiny so popular? Well, it’s a winning combination—as far as the Thai viewers are concerned anyway—of comedy and time-travel (mixed with soul-swapping/reincarnation) and fantasy that’s set in the period in history regarded by many as one of the most glorious eras in which Siam was a powerful and prosperous kingdom in Southeast Asia. You have elements of ancient history, language, archaeology, and pretty realistic reenactments of actual historical events (even though you may want to take their interpretation of some historical events and portrayals of some historical figures with a grain of salt). You have a reinforcement of old superstitious beliefs and the romantic notion of how if two people are destined to be together, there’s nothing—not even the difference in space and time—that can keep them apart. Throw some good-looking actors into the mix and boom.

Here’s my synopsis—so short you may find it rude: The soul of Ketsurang, a young field archaeologist from the modern era who specializes in the Ayutthaya period of Siamese (Thai) history (mid-1300s to mid-1700s CE), gets stuck in the body of Karaket, a woman who lived in 17th century Ayutthaya. So here we have a modern-day woman kinda sorta time-traveling [1] to an ancient era when things we take for granted today like undergarment, feminine products, en-suite bathrooms, purified drinking water, or big, fluffy pillows didn’t exist. The inevitable anachronistic elements, including language and worldview, lead to all kinds of hilarity.

Anyway, back to our girl Ketsurang. Being in Karaket’s body means she is also linked to Karaket’s betrothed, the son of an important aristocratic family, one of the ministers in King Narai’s court, and a future member of the 1686 Siamese embassy to France during the time of Louis XIV. And most of the story of Love Destiny is what takes place while Ketsurang lives (in Karaket’s body, that is) with his family, one of the elites of Ayutthaya (how convenient…). This means, in Karaket’s body, Ketsurang gets to enjoy not only the wealth and privilege that come with the sakdina system, but also access to key historical figures all of whom are among the most influential and powerful people in those days. (She even got to be BFFs with Maria Guyomar de Pina, the woman whom I’ve told you about in the Bangkok book.) In other words, Ketsurang, a 21st century archaeologist, gets to live the ultimate fantasy that I believe all archaeologists and philologists harbor, and that is to see with your own eyes and to experience firsthand the things you’ve thus far learned about solely from ancient witnesses. I. Know. That. Feeling.

And, finally, ladies and gentlemen, we’ve come to the main point of this post.

Unlike the rich khun nu of the 80s and 90s TV series, Ketsurang (again, in Karaket’s body) is portrayed as very enthusiastic about food and eating [2]. In her 21st century life, she has also been taught several basic skills, including how to cook, by her mother and grandmother. All of these things come in handy as she lives her life in 17th century Siam. In one episode, she teaches the ancient Ayutthayans how to filter water. In another episode, she points out that Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease which can be ameliorated by eliminating larval habitats around the house and sleeping in a mosquito net. In another episode, she teaches the servants how to make Western-style cotton-filled pillows. When a Western teacher trains the members of the Siamese embassy to France prior to their voyage, she is there to help translate.

But the most entertaining contribution Ketsurang has made to her ancient friends and family is to introduce them to a few of her favorite Thai dishes that would not become known—let alone popular—for another few hundred years.

In this clip, Ketsurang brilliantly takes advantage of the fact that she’s in Ayutthaya and teaches the ancient Ayutthayans how to prepare their famous river prawns (read what I’ve told CNN here) in a way that they did not back then: grilled and served with a spicy seafood sauce. This is an attempt on her part to win over her future mother-in-law who, at that time, doesn’t know it’s Ketsurang who lives in Karaket’s body and still can’t see past Karaket’s character (which is cruel and abhorrent).

Notice in this clip:

1. The use of salt. Salt is optional in this recipe. When I make this seafood sauce, I don’t use salt. But you can. Those of you who know Thai food well will probably find it hard to believe how many times people have written me in the past several years asking (sometimes in a not very nice way) why some of my Thai recipes call for salt. This comes from a misconception that salt is used solely in Western cuisines and that a Thai recipe can only be “authentic” if its source of salinity is fish sauce or some sort of fermented marine lives. (Well, how do you think fish sauce is made?)

2. How the Thai people use their mortar and pestle. They pound. They don’t muddle.

3. At 1:18, how her future mother-in-law looks so pleased with the dish, though at 1:32, she tries not to show it. At 2:16, however, you can hear her mentally say forget it while gleefully reaching for another grilled river prawn. Understandable. I would have done the same.

4. At 1:22, her future father-in-law (played by the ever-so-handsome Nirut Sirijanya whom you have seen in this jok scene from the Hangover 2) is also pleased with the dish.

5. How the Siamese eat with their hands. Notice also the bowls of lime-scented (sometimes flower-scented) water which the servants set out for them to wash their hands in before and after a meal.

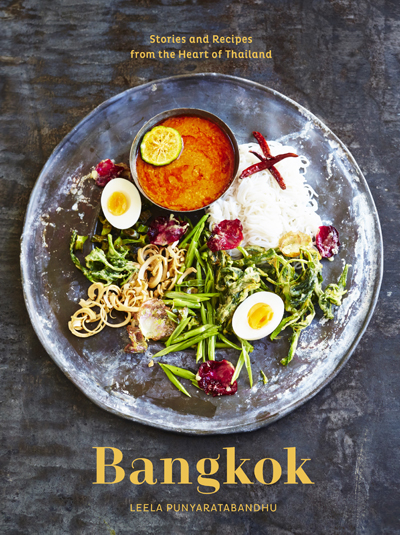

In this clip, Ketsurang sees some fresh green mangoes and starts craving mamuang nam pla wan, green mango slices with salty-sweet caramel (recipe in my book, Bangkok). So she introduces her friend, Chanwat, to it. Chanwat and her contemporaries, of course, have never heard of this dish.

Notice in this clip:

1. At 0:38, Ketsurang uses the word “saep,” a word in the Northeastern dialect that means delicious. However, lately people from all regions of Thailand, especially the Centralites, have borrowed it from Isan and broadened its semantic range to include the meaning of something strongly seasoned—spicy, titillating, and satisfying (this also applies to non-food-related things and, um, sometimes actions). You’ll sometimes see it spelled with the letter z (as in zap, zaep, or even zapp) in Thai restaurant menus or Thai restaurant names. The z sound doesn’t exist in Thai, so these spellings can’t be regarded as legitimate in any way. Some people just use it as an intensifier of sorts.

2. Ketsurang realizes that dried shrimp isn’t widely used in that area back then. Luckily, at 4:34, she chances upon some dried fish (most likely dried freshwater fish which would have been abundant in Ayutthaya), so she uses them instead. If you have shellfish allergy, this is an option for you.

3. At 6:49, a demonstration of how to eat this dish, courtesy of Ketsurang in Karaket’s body.

4. At 7:01, there it is again—saep!

But the ancient Ayutthayans aren’t the only people learning about new dishes, in one episode, her future mother-in-law teaches Ketsurang how to make mu sarong which is basically seasoned pork sausage rolled into bite-sized balls and wrapped with thin wheat noodles (mi sua) into what looks like little skeins of yarn (some see them as little sepak takraw balls).

The dish is not complicated to make, but it’s time-consuming—one of those things that take an hour to make and a few seconds to polish off. The part that will make you sit and work for an hour is the wrapping. You need to form the pork sausage into tiny, bite-sized balls. That takes a few minutes already. Then you need to wrap the noodles around each pork ball—one by one—which takes some patience and skills.

Patience, I have. Skills? When it comes to the beautification of food, not so much. Some people will tell you that for mu sarong dumplings to be considered good-looking and properly prepared, they need to look like this—that is, neatly and entirely wrapped with not even one end of the noodle strands sticking out anywhere.

I’ve had mu sarong expertly wrapped like that and I’ve had mu sarong dumplings that come fashionably disheveled as well. And I declare the latter better. Why? Surface area. More surface area means more crispiness. Noodle strands that stick out create more surface area and more crispy bits. Leaving some tiny parts of the pork balls exposed also helps you see better when the meat is sufficiently cooked. I don’t see the need the wrap it tightly and entirely. In fact, when you wrap the noodles too tightly and too neatly, they form a shell that becomes too thick and too hard once the dumplings are fried, and it’s this thick shell that keeps the pork inside from cooking properly.

This is one of those times where a lack of skills actually leads to better end results. I’m pretty sure I’m not making an excuse here.

____________________________________________

[1] This is nothing new, however. Time travel novels (and dramas based on them) aren’t new in Thailand. Thawiphop (literally “two worlds”), a novel about a modern woman traveling to 19th century Bangkok through a magic mirror, has been popular for decades. But while Two Worlds is set in the sober time when the threat of Western colonialism was regarded as the most serious national issue and while the time-traveling protagonist of Two Worlds is portrayed as using her knowledge of the modern era and her personal skills to help steer Siam through the storm, Love Destiny is more of a comic fantasy story wherein the protagonist isn’t directly playing a role in history—unless you count the introduction of several modern words straight out of Urban Dictionary to 17th century Siamese.

[2] This is where I sigh. The reason Ketsurang in Karaket’s body isn’t as food-averse as the stereotypical female lead characters is because—this is where I sigh again—in her 21st century life, her character is described as food-motivated. Ketsurang wears thick glasses; she is portrayed as studious, semi-nerdy, homely looking, and, of course, overweight (according to the Thai standard, anyway). There’s a scene showing her in the present time eating a meal with her mother and grandmother where she asks for more food and gets immediately reprimanded by her mother who is afraid she’ll get even chubbier. And there’s that first moment when Ketsurang realizes she has time-traveled to an ancient period and is stuck in Karaket’s body when she jubilantly blurts out, “I’m thin!”

Well, nothing wrong with that, I guess. But here’s an idea.

Can someone come up with a Thai movie or a drama series in which plus-size girls don’t need to be in a perpetually jolly mood or act like a court jester to be found lovable? How about a movie or a drama series in which a plus-size girl can find true love without having to have her soul put in the body of a thin woman first? If destiny—assuming it’s a thing—is so powerful, this shouldn’t be a problem, right?

- 4 large cloves garlic

- 1 teaspoon whole white or black peppercorns

- 2 medium cilantro roots, finely chopped, or 2 tablespoons finely chopped cilantro stems

- 1 pound ground pork

- 1 tablespoon fish sauce

- 1 large egg white, beaten lightly with a fork

- 12 ounces fresh very thin wheat noodles or 6 ounces dried noodles, soaked in lukewarm tap water until pliable, drained, and blotted dry

- Vegetable oil for deep-frying

- A pair of wooden chopsticks

- Thai sweet chili sauce for serving

- Grind the garlic, peppercorns, and cilantro roots into a fine paste. Mix the paste into the ground pork along with the fish sauce and egg white. Use your hand to knead and squeeze the pork mixture until it feels sticky—the same consistency of Italian or breakfast bulk sausage. Cover and chill 30 minutes.

- Form the pork mixture into small balls, each measuring just a tad shy of an inch in diameter. Be sure to roll each one between your palms to smooth the surface and form a tight ball. If the balls are loosey goosey, you'll have a very hard time wrapping them with the noodles and keeping them intact while deep-frying them.

- Grab 3-4 strands of noodles, line them up, and wrap them around one pork ball, pushing them lightly into the surface of the pork as you go to secure them. Go around the pork ball a few times until you get what looks like a skein of yarn that isn't too disheveled or or too neat. Tuck in the ends of the noodle strands and place the dumpling on a large platter seam side down. Do this with the remaining pork balls. Yup, you'll be sitting here for a while.

- Pour enough of the oil into a wok so it measure about 2 inches deep. Set the wok on medium heat. Place a paper towel-lined tray next to the stove.

- When the oil is hot (but not to the point where it smokes), use the wooden chopsticks to carry one dumpling at a time to the oil. Keep squeezing the dumplings lightly with the chopsticks even after it has gone into the oil; this is to keep the noodle strands in place. Do this for 4-5 seconds, then let that dumpling go. Repeat with another dumpling and keep going until you run of dumplings to fry (yup, you'll be standing here for a while). Don't overcrowd the wok, though, and don't use high heat (otherwise the noodles will burn before the pork inside is cooked).

- Transfer the dumplings that has turned golden brown to the prepared tray to cool to just a little warmer than room temperature.

- Serve the dumplings as an appetizer with Thai sweet chili sauce on the side (or a mixture of Thai sweet chili sauce and Thai (not American) sriracha as I've done here).

Comments are closed.