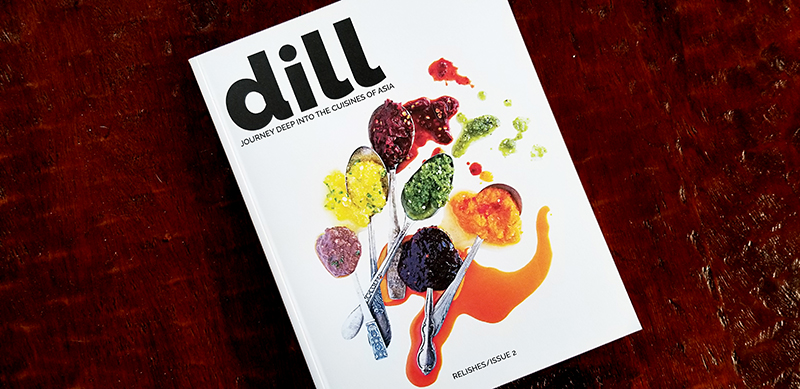

Around this time last year, I met with some of my friends who are part of Dill Magazine to talk about something I had wanted to see for a long time: a story on Thai relishes, nam phrik. These dishes form the most significant segment of Thai cuisine, but they’re the least understood and the least appreciated. I thought it was about time this changed.

Western food media doesn’t like to publish a story like this. It’s too niche. It doesn’t have a broad appeal. For them, it doesn’t make sense to dedicate their precious real estate on something most people don’t already know and love. Nam phrik, therefore, hasn’t received a lot of coverage in mainstream publications, and when it does, the coverage doesn’t go deep and is often rife with misinformation.

I took the idea to Dill, because of this. I wanted to see a story on nam phrik; I wanted it written with competence, understanding, and insight; and I knew the group behind Dill was capable of pulling this off. Even though they’re new and small and don’t have the resources of a large publication, they don’t shy away from specialized materials. I also know the Dill people don’t present niche stories in a “hey, look at the bizarre foods these other people eat!” manner either. In other words, I knew this story would be in good hands.

I also suggested to them that this story be written by my friend Mike Sula, Chicago Reader’s senior writer and lead restaurant critic. At that time, Mike had never been to Thailand before, but his understanding of Thai food from covering Thai restaurants in Chicago had already surpassed that of the many whom I’ve met, who have lived there for years. Mike is observant and perceptive—someone who sees and comprehends things without those things needing to be obvious and loud. Mike is a quiet and humble learner yet a confident and engaging storyteller. He’s also one of the best writers I know. And since both the Dill team and I wanted the story written from the perspective of a non-Thai exploring the world of nam phrik, we agreed that Mike was the perfect person for this.

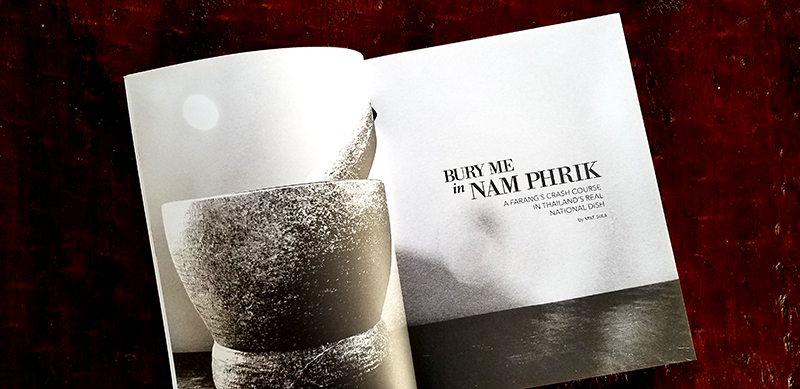

So Mike went to Bangkok last fall and met with several well-respected home cooks and chefs. The James Beard Award winning writer came back with Bury Me in Nam Phrik: A Farang’s Crash Course in Thailand’s Real National Dish, published in Issue #2 of Dill Magazine, entitled Relishes. It is the most illuminating, the most well-researched piece on the subject ever published in the English language. And it’s darn fun to read.

Just for fun, I thought I’d ask Mike a few questions about his experience working on this piece. Here’s what he says. (Note: Mike’s answers refer to a few individuals whom he had interviewed during his time in Thailand. These are the people he has introduced in detail in the article.)

What did you know of nam phrik before you went to Thailand?

Relatively little. I made nam phrik phao years ago from a cookbook, the title and author of which now escape me (it’s in a box somewhere in the basement), but mostly I just bought that in jars and used it in stir-fries or soups. I think I might have become aware of it as a vast category of different dishes after first encountering the lon at the late Sala Bua in Chinatown and then discussing that with you. I believe that’s when I began to get an inkling that it wasn’t just a condiment, but a dish unto itself with a whole ritual way of eating attached to it. And then I believe I got into it a bit when I interviewed Chef McDang. But all of that was mostly academic. I’d never experienced it in very much variety, apart from the little sampler pack you once sent me. But even all the preparation I made for this assignment couldn’t ready me for its vast diversity and also its fundamentals. I’m aware that I really still only got a glimpse of them.

What were you most curious about when it comes to nam phrik? Did you get all your questions answered in the course of working on this story?

No way. There’s never enough time when you’re traveling somewhere new. Like a lot of new experiences, it only underscored how much more there was for me to learn. Even among the chefs and cooks—authorities—I met, there is so much variability and contradiction in what a nam phrik is, its origins, its purpose, that I began to suspect that there weren’t many absolutes.

How did you feel when you got this nam phrik assignment? What were your expectations? What were you most excited about? What were you afraid of?

I fully expected it to be a singular, unique experience. It was! My biggest fear was that I wouldn’t represent it properly—that my inability to read and speak Thai would make me miss out on critical information. I still worry about that.

I thought going in that I would eventually be able to present a tidy nam phrik taxonomy, but I was quickly disabused of that idea.

How did you feel the first moment you walked into Krua Apsorn?

That was my very first interview, and despite your best efforts to put me at ease, I was still intimidated by Pa Daeng’s reputation. But I soon recognized that my discomfort, unfamiliarity, and anxiety had storytelling potential, not just for comic effect, but also as a way to ease readers into the universe of nam phrik that still seems to defy categorization. At the end of that encounter, I think I knew that I would introduce the whole story with it.

Was there anything you learned during that week that surprised you, amused you, made you stay up at night thinking of? Give me some of the behind-the-scene highlights.

When Ning introduced me to the vegetarian nam phrik with mushrooms subbing for dried beef and soybeans subbing for pla ra, I was fascinated. And I was disappointed that I couldn’t get the recipes for those meatless nam phrik, because they were very convincing and tasty. Also her (controversial? dubious?) theory that nam phrik was originally a way to disguise the consumption of animal protein, fed into this preconception I had going in that pounding various ingredients into a relish had to have some deeper purpose and meaning beyond the nutritive.

Similarly, I was consumed by the novelty of Torroong’s red fermented tofu lon and her nam phrik turnaround, the latter tasting like my mom’s raw ginger snap dough. Maybe that was the jet lag.

Yeast’s story about how he still gets lots of foreign customers at the Summer House Project ordering their own individual bowls of curry made me sad and, for that reason, stuck with me.

Here’s a hypothetical question. Imagine that the first wave of immigrants from Thailand were filthy rich, that they opened restaurants as a hobby, and that they didn’t give a single hoot whether their food would please the American palates. Imagine they started out serving Thai food as the Thais really knew it which, of course, must have included the various nam phrik instead of the sometimes watered-down, sometimes sinicized group of dishes that had come to define a typical Ameri-Thai restaurant menu. Would the Thai restaurant industry in the US have been DOA?

Has that ever happened before with any cuisine that came to America? French food maybe? Maybe Thai food in the U.S. would be on a par with French food—still after all this time a relatively upper class cuisine in reputation—as opposed to something that most Americans consider to be cheap eating. Going out for Thai might be this rarefied special experience that people would save for birthdays and anniversaries, feasting on grand samrap with boat relish at the center like little royals.

We didn’t really talk about the recent Vice story about how the Thai government subsidizes so many Thai restaurants abroad, and I don’t know to what extent that’s true, but I do wonder what would happen if they put some of those resources into a big nam phrik push. I didn’t get into it in the story, but one thing I wasn’t aware of was that pad thai’s prevalence abroad was because it won a government sponsored contest to choose the Thai national dish. Do I have that right? Pad thai is fake news!

Your research led you to historical records showing how 17th century French explorers weren’t impressed with funky Thai ingredients like pla ra (fermented fish) or kapi (shrimp paste) which are the backbones of most nam phrik. But is funk the only issue Westerners have when it comes to nam phrik?

I think capsaicin as well as raw garlic and shallots will also be a barrier to it hitting the mainstream. Recipes with cooked ingredients will probably be first, à la nam phrik phao.

If Westerners are going to get into it en masse, they’ll need to learn how to khluk (Leela’s note: there’s a Q&A with me on the topic of khlukking in the same issue of Dill). I suspect as a culture we don’t yet have the mindset for that kind of conscious eating—when you’re deliberately creating customized bites with a little bit of this and a little bit of that. We still just want to shove everything into our face holes at once. That is unless, you know, someone sneaks it in and blows up with a nam phrik ong taco truck (Leela’s note: nam phrik ong is a pork-tomato relish from the north of Thailand; there’s a recipe for it in the second issue of Dill).

Mike’s story in Dill comes with 15 recipes that came from the people whom he’d interviewed while in Thailand as well as from the magazine’s test kitchen. You can find out more about Dill’s Relishes issue, Thai nam phrik, and other delicious Asian condiments and relishes here. If you’re a fan of Asian food and, especially, if you’re in the business of making or writing or speaking about or doing anything related to Asian cuisines, I don’t think you want to ignore this great magazine (full disclosure: I know some of the people on the team personally).

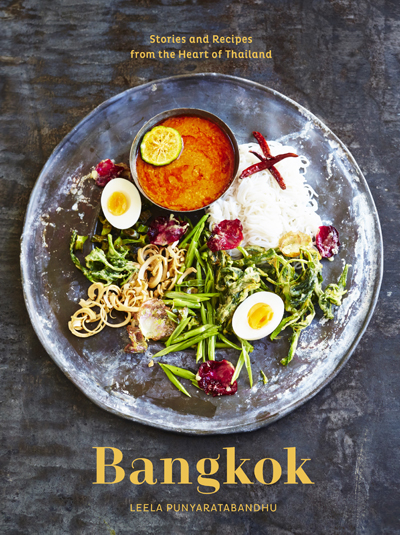

You’ve seen a few nam phrik recipes on my blog before—from the (ghost-approved) pungent shrimp paste relish with lime zest to the mild and creamy lon made with salmon. My first book, Simple Thai Food, contains a recipe for nam phrik phao (Thai chile jam) and shrimp-coconut relish both of which are great for those beginning to get into the world of Thai nam phrik. In my latest book, Bangkok, I didn’t hold much back and gave you several more challenging relish recipes, including the famous hell relish and the elaborate boat relish.

But here’s an easy recipe which requires no cooking (except if you want to serve it with blanched, steamed, or pan-fried vegetables on the side). All of the ingredients are pretty easy to find (see my recommendations here). One thing to be careful about, though, is the type of pork rinds you want to use. While the type you can find at most gas station minimarts works fine (as long as it’s unseasoned or lightly seasoned with only salt), the best type is the type you’d typically find at Latino or Asian stores which comes with a little bit of fat attached to the skin (as shown in the picture above). Before you add the pork rinds to the relish, open the bag and taste a few to make sure they aren’t old and rancid. If you want to go an extra mile, use homemade pork cracklings, a delicious byproduct of lard making (there’s a recipe for that in the Bangkok book).

Serve the nam phrik with lots of rice, as it should be, and a platter of your favorite vegetables. Crisp, raw vegetables like cucumbers, radishes, sweet peppers are great. Steamed pumpkin adds a nice texture and sweet flavor. Blanched okra—those are good too. Radicchio stands in for the bitter Thai herbs and shoots I can’t find over here. The ramps? Do whatever you’d like with them. Pickling works. Light sauteing works as well. This is the fun part I’ve talked about in the “Khluk” section of the magazine.

Be sure to season it the way most Thai relishes, i.e. with a heavy hand. If you can eat a spoonful of it without having to mix it with maybe 4-5 bites’ worth of plain rice, and if you think it tastes just right, you’ve underseasoned your nam phrik by a lot.

- 6 large cloves garlic, peeled

- 1 teaspoon packed Thai shrimp paste

- 4-5 fresh bird's eye chilies

- 3 teaspoons packed palm sugar or 2 teaspoons packed brown sugar

- 1 tablespoon salted soybean paste

- 1 ounce shallot, peeled and cut into small cubes

- 1 ounce pork rinds (unseasoned or lightly salted)

- ¼-1/3 cup lime juice

- Fish sauce, if necessary

- Fresh and lightly cooked vegetables

- Pound the garlic and shrimp paste in a mortar into a smooth paste. Add the chilies and pound into match head-sized pieces. Add the sugar, soybean paste, shallots, and pork rinds and pound until well mixed and the pork rinds turn into fine crumbs.

- Stir in ¼ cup of the lime juice. Taste. Add more lime juice if needed. If it's not salty enough (unlikely, especially if you use commercial pork rinds which are almost always salted), add fish sauce. The relish should be salty first, then sour, with sweet trailing behind, and it should very strong. The texture should be like that of thick hummus. If it's too loose, stir in more pork rind crumbs. If it's too pasty, stir in a little warm water.

- Serve with rice and vegetables.

Comments are closed.