I recently fell in love with a book. I’m still head over heels as I’m typing this sentence.

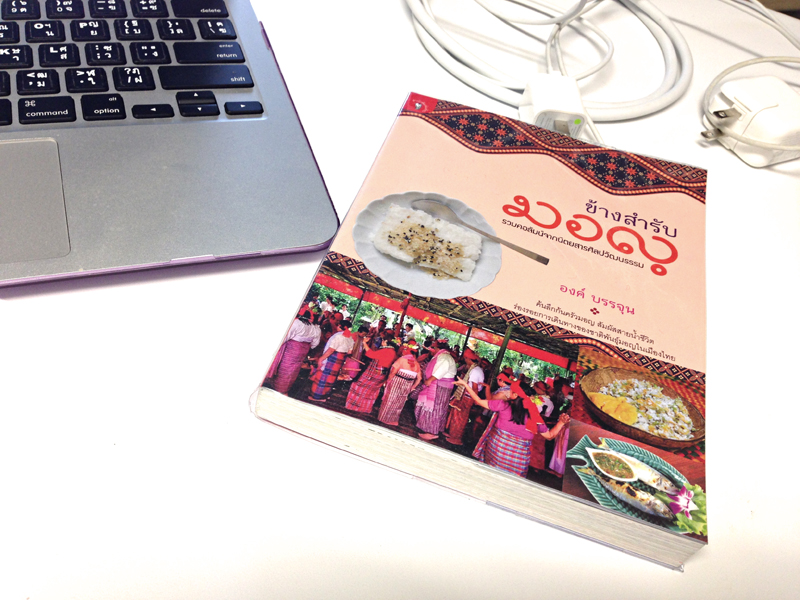

Long story short, I popped into a Kinokuniya during a quick layover in Bangkok early this summer in hopes of finding something tiny but texty and thrilling* to read on the 4-hour plane ride I’d catch later that evening. No more than 5 minutes later, I walked out with a copy of Khang Samrap Mon (ข้างสำรับมอญ)**, a pocketbook — still shrink-wrapped — with nothing that appealed to me on a quick glance other than the title and the author’s vaguely familiar name.

Not only was the book devoured in one sitting as planned, it was also constantly by my side as I was hopping from place to place in East and Southeast Asia in the following 3 months. All sorts of brutal acts like double- and triple-underlining, highlighting, dog-earing, excessive exclamation pointing, and ranty, monologic marginal-notating had been committed by me against the poor book. But in the process, I had learned so much about the culture and food of the ethnic Mon in Thailand.

I even made a phone call to its author, Ong Bunjoon, a historian and a scholar who is doing research on the ethnic Mon in Thailand. You see, my original plan was to, in a calm and dignified manner, congratulate Ong on a book well done as well as to get his comments on certain things. But, of course, as soon as Ong said ‘hello’, I started incoherently gushing over his book like a smitten schoolgirl.

Once I got that out of my system, we talked at length about things mentioned in the book: food, culture, the archaicization of places and the preservation of old communities for our nostalgic pleasure (not to mention commercial gain), and the ethnic plurality of the Thai society (which is not acknowledged nearly enough). We also discussed etymology and some of the linguistic fallacies that he and I have noticed in some of the popular writings related to Thai and Mon food.

It was a pleasure for me to find out that both in his writing and in person, Ong is someone who says it like it is and does it so humbly, eloquently, and — this is rare among academics — humorously.

Khang Samrap Mon is a collection of articles focusing on the food of the Mon in Thailand. Ong is also a Thai of Mon descent. His stories come from the early years of his life that were spent around the rivers and canals on the west side of central Thailand. This is the area where you’d find a high concentration of Mon communities many of whose members, including Ong’s parents, made a living selling earthenware on small rice barges in the old days. But even though the Mon have long assimilated into the general population in Thailand, they still retain the language and the culture. And, as Ong indicates throughout his book, the food is something the Mon have preserved amazingly well amidst the dizzying pace of globalization.

I feel bad for bringing a great book to your attention only to tell you that you can’t enjoy it unless you read Thai. So let’s consider this post merely an introduction – a prelude of what’s to come. I’ll tell you more about this book and the great recipes in it in subsequent (but not consecutive) posts. As we continue, I’ll also go deeper into the topics of culture and society that Ong has brought up in this book.

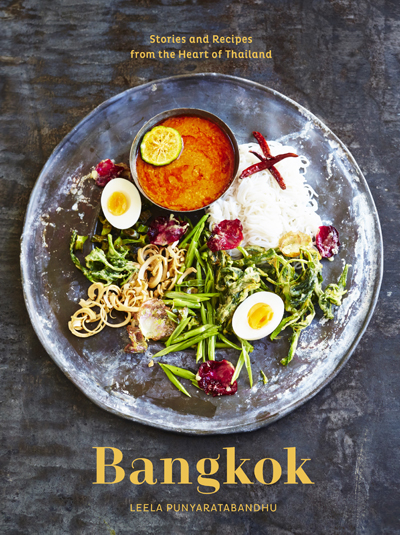

In the meantime, I’d like you to give one recipe from the book a try. This fish sauce-based dipping sauce (nam pla mon) is one of the iconic Mon dishes and the first recipe to appear in this book. Ong suggests that you do what the Mon do which is to serve it alongside grilled fish, more specifically short-bodied mackerels (pla thu).*** He recommends that the fish be grilled just until the flesh turns pink — medium well, to be exact. But the sauce is highly versatile, so you will find many uses for it. As you see here, I’ve served it with steamed seafood, but any cooked meat that’s minimally seasoned would work well too. (I’ve had it once with store-bought rotisserie chicken and sticky rice; it was delicious.)

Most of the ingredients in the recipe aren’t difficult to find. Many of you can’t find fresh kaffir lime leaves, so I have listed those as optional. The other rare ingredient is krachai (fingerroot or wild ginger). Now, this one I’d like to encourage you to put some effort into sourcing, because this is the one thing without which this dish can’t be what it is. Fortunately, like most rare ingredients which were once hard to find, most well-stocked Asian grocery stores carry one form or another of this rhizome: fresh, frozen (vacuum-packed in a plastic bag), or slivered and brined (in a glass jar). Fresh is, of course, best, but I have tested this recipe with the other two options and it works just fine.

The last thing is to be careful with the type of tamarind concentrate you use. Your best bet is to make your own tamarind pulp. Failing that, stick with a Thai brand such as Dragonfly, Garden Queen, Por Kwan, etc. (I strongly recommend against the dark, syrupy, molasses-like tamarind concentrate brands used in Indian cooking. There’s nothing wrong with them, but they’re not made for Thai cooking and will result in the flavor and consistency that this recipe does not intend to create.)

Other than that, this sauce, as you will see, is a cinch to make. There’s no cooking involved. And it’s all done in 10 minutes – less if you’re good at chopping things.

______________________

* This mostly describes a pocketbook that is small enough so I can 1. fit in my purse, and 2. read from cover to cover in one sitting, but is also 1. textually substantial (in other words: the book is already small; it shouldn’t contain fluff or superfluous photos), and 2. fascinating enough to hold my interest thereby making the cover-to-cover-in-one-sitting reading not only possible but pleasurable.

** Khang = by (in the locative sense), near, beside; samrap = a meal ensemble, a spread of various rice accompaniments; mon = the ethnic Mon (genitive). The translation of the title can be smoothed out to “At the Mon Table”.

*** In fact, Ong got this recipe from a restaurant in Amphawa district on the Mae Klong river where, pla thu, short-bodied (aka Siamese) mackerels are celebrated. Over in the province of Samut Songkhram, they even hold a big pla thu festival every winter when the fish are at their meatiest, fattiest, and best. They take their fish pretty seriously in that part of the country.

_________________________________________

PRODUCTS THAT HELP YOU CREATE THIS RECIPE

- 3 large stalks lemongrass

- ¼ cup fresh bird’s eye chilies, stemmed (or 2 red or green Serrano peppers, stemmed and roughly chopped)

- 1 head garlic, separated into individual cloves and peeled

- 3 small shallots (weighing about one ounce each), peeled and roughly diced

- 2 sticks of fresh or frozen krachai, wild ginger, roughly sliced crosswise (or ¼ cup rinsed and well drained wild ginger slivers in brine)

- ⅓ cup tamarind pulp (see post)

- 2 tablespoons palm sugar, packed (or 1 tablespoon light brown sugar, packed)

- 3 tablespoons lime juice

- ½ cup fish sauce

- 3 fresh kaffir lime leaves, deveined and sliced into very thin strips (optional but highly recommended)

- Trim the tough leaves and the hard, knobby root ends off the lemongrass stalks. Slice them crosswise as thinly as you can, starting from the bulbous end, until the purple rings disappear (reserve the woody, fibrous parts for other purposes or simply discard them). Measure out ¼ cup of lemongrass slices to use here. (This means you may or may not use all 3 stalks, depending on how large and tender they are. It’s better to have more than you need, though.)

- Place the lemongrass slices along with the other ingredients, except the kaffir lime leaves, into a blender or a food processor. Blend until all of the ingredients have become roughly the size of a match head. (This step can be done in a mortar as well; just grind your fresh ingredients without the fish sauce, sugar, lime juice, and tamarind, then mix them in later.)

- Do a taste test. The sauce should be equally salty, sour, and sweet. Adjust the seasoning, if necessary. Once that's done, stir in the kaffir lime leaves.

- The sauce should be used right away. But it can be stored in an airtight container and kept chilled for a week. (I figure it can also be frozen, though I have never done that and, therefore, can't speak about what freezing may do to the quality of the sauce.)

Comments are closed.