No thinking person would ever take the words of Anna Leonowens as the singularly, unquestionably authoritative source of information on mid-1800s Siam much less regard the musical the King and I, or the film adaptation thereof, as historically accurate—or even factual. But can one learn to make Thai food from legendary actor Yul Brynner?

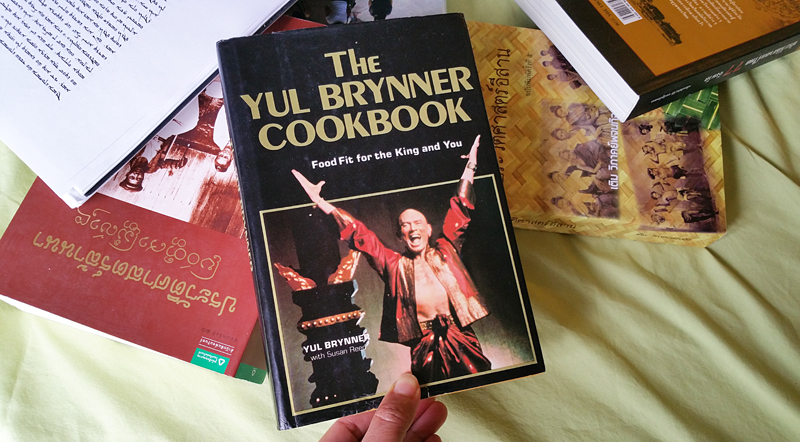

That was the question on my mind as I began leafing through The Yul Brynner Cookbook: Food Fit for the King and You, the book Brynner co-authored with Susan Reed, which I had recently discovered—three decades after it was published.

“What keeps the magnetic and energetic star of The King and I […] going?” The inner flap of the book asks before answering its own question: “Good food, obviously. ” It then goes on to inform us that Brynner was “a true gourmet, reflecting his Gypsy-Swiss-Mongolian heritage and his international citizenship.” This cookbook, therefore, aims to present hundreds of his favorite international dishes “so that you, too, can eat like a king.”

Curious, I spent the next few hours with the book, getting to know it—getting to know all about it—to see if it would be precisely my cup of tea.

The book covers dishes drawn from Russian cuisine, Japanese cuisine, Gypsy cuisine, Swiss cuisine, Chinese cuisine, French cuisine, and Thai cuisine. The section on Thai dishes is the smallest of all and tucked away in the very back. I’m not sure what this means given how prominently the book hints at Brynner’s Siam-related role. Regardless, I went straight to that section.

Not without a fair amount of skepticism, though. With the book written back in the early 80s when words such as “exotic” or “Oriental” were still commonly used, when the lines between the various Asian cuisines were still blurry to many people, what would it contain? (To be fair, if you go through Thai cookbooks from the same period, you’ll find that, apparently, the lines between the various western cuisines were blurry to many Thai recipe developers as well.) With essential ingredients, such as fish sauce and prepared curry pastes, not being available in every supermarket like they are today, what would Brynner’s Thai recipes look like?

Right away, I found pieces of misinformation scattered throughout the introduction, such as “soup is considered a beverage” and “because of the hot and humid climate, Thailand benefits from several rice harvests a year,” et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. The sweet and sour mee krob (mi krop) recipe, for unknown reasons, contains no source of acidity. The salad recipe, named “Thai Salad” and described as ‘typical,’ calls for peanut oil, egg yolks, and lemons. There is a “Hot and Sour Soup” that doesn’t resemble anything I’ve seen anywhere. And in case you’re forgetting you’re reading a book from decades ago, the maraschino cherries on the list of recommended garnishes will instantly jog your memory.

But there are several things to commend. For example, efforts go into teaching you how to make fish sauce—a hard-to-find ingredient in the early 80s, no doubt—out of soy sauce, anchovy paste, and water. I wouldn’t recommend the same thing, but I applaud the thought that went into solving the problem creatively. The way the process of extracting coconut milk from a mature coconut is described is spot on. Also, except for that one salad recipe, peanut oil isn’t used anywhere. Nowhere does rice vinegar make an appearance either. (Admittedly, the last two points are somewhat subjective; these are my personal pet peeves. These two ingredients represent more what some recipe developers assume must be used in “authentic” Thai cooking than reality. But let’s keep this discussion for later.) The tom yam recipe looks great. And the reference to a garnish of fresh cucumber slices with serrated edges tells me Brynner was quite observant.

After all this, the only way to know if the recipes are any good would be to try them out. Unfortunately, since I’m currently traveling and occasionally sleeping on my relatives’ sofa, the most I can do right now is testing one recipe. So I picked “Chicken with Yellow Curry” on page 204 to test. It seemed easy enough.

Let’s take a look at the ingredient list.

3 cups coconut cream

1 large onion, sliced

1 large bay leaf

2 pounds chicken in pieces, with bone and skin removed

½ teaspoon turmeric

½ teaspoon cinnamon

1 teaspoon coriander

4 dried red hot chili peppers

1 clove garlic

½ fresh lime

When your life revolves around cooking or recipe testing, you can take a look at a recipe—sometimes even just the ingredient list!—and have a pretty good idea how the dish will taste. In this case, the alarm in my head went off right away: there’s no source of salinity in this recipe. (Interestingly enough, the only savory recipes in this section that don’t call for anything salty are the curries. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯) Also, the one-sentence head note doesn’t make much sense to me: “This curry is mild and has a sweet taste because it is cooked with cinnamon.” Not because it contains half the number of dried chilies another chicken curry recipe on the previous page, described as spicy, does? Not because it contains the naturally sweet coconut milk? Cinnamon? A whopping ½ teaspoon of it?

Is a puzzlement.

But I went ahead with it anyway even though I was a little bit afraid. But do you know what I do when I’m afraid? I whistle. Whistling a happy tune, I mentally pushed aside everything I know about how to make a coconut-based Thai curry and followed the recipe as closely as I could. Boil the coconut milk first, add the chicken, then throw in the dry spices? I did that. Sprinkle some lime juice over the curry just before serving? It’s not done in Thailand, but I did it too. The recipe doesn’t tell you what to do with the peppers and the garlic, so I just ground them up into a paste. The only departures were: 1. I added a couple of tablespoons of fish sauce—I had to—and 2. I used bone-in chicken thighs for maximum flavor, leaving the skin on half of them.

This book … it will not always say what you would have it say. But now and then it’ll say something wonderful. Because the result? Even though Yul Brynner’s yellow curry chicken doesn’t look or taste like the Thai yellow curry I know, it’s delicious. Very much so. The two people who shared this pot of curry with me can testify to that. We polished it off in just minutes. It was a success. (Now, shall we dance?)

Just as I don’t recommend learning the history of Thailand from the King and I, I don’t recommend learning how to make Thai food as the Thai know it from this book. But as historically dubious as the musical is, its artistic and entertainment values are undeniable; Brynner was also brilliant in it. Likewise, as unreliable as this book is as a Thai cooking resource, I now know it contains at least one great recipe worth sharing and I can’t wait to try more from every section in it. And just as I think the King and I was never intended to be anything but a source of entertainment, I think Brynner’s cookbook was simply meant to be a collection of dishes that he liked and wanted to share with his fans.

__________________________

Source: Yul Brynner and Susan Reed, The Yul Brynner Cookbook: Food Fit for the King and You (Briarcliff Manor: Stein and Day, 1983).

- 8 large bone-in, skin-on chicken thighs (about 3½ pounds)

- 2 large yellow or white onions

- 1 teaspoon ground turmeric

- 1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

- 1 teaspoon ground coriander

- 4 large cloves garlic, peeled and minced

- 8 small dried red bird's eye chilies, crushed

- 3 cups coconut milk mixed with 1 cup water (Total 4 cups)

- 3 dried bay leaves

- 2 tablespoons fish sauce (or more, to taste)

- 2 cinnamon sticks, optional

- Juice from one lime

- Decide if you'd like to keep the skin on the chicken. If not, remove it. Then cut each chicken thigh through the bone in half; arrange in a single layer in a large sauté pan.

- Peel the onions. Halve them lengthwise. Put the onion halves, cut side down, on the chopping board and cut them lengthwise again into 1-inch slices. Scatter them on top of the chicken.

- Combine the ground turmeric, ground cinnamon, ground coriander, minced garlic, and dried chilies with 2 cups of the diluted coconut milk; pour the mixture over the chicken and onions. Throw in the bay leaves and cinnamon sticks. Add the fish sauce.

- Put the pan over medium-high heat. Once the liquid boils, turn the heat down to medium; cook, covered, for 30 minutes.

- Skim off excess fat on the surface, if necessary. Turn the heat up to medium-high and cook, uncovered, for about 30 minutes. Be sure to give the curry a stir every 5 minutes or so and skim off the fat.

- Once the liquid is half its original amount, stir in the remaining coconut milk; heat through and remove from heat. Remove and discard the bay leaves. Taste to see if it needs more fish sauce; don't forget to account for the bland rice the curry will be served with.

- Stir in the lime juice. Serve with rice.

Comments are closed.