Here’s a modern-ish Isan dish that would be perfect for this time of year when the temperature is beginning to drop in the Northern Hemisphere.

Essentially Isan shabu shabu or hot pot Isan-style, jim jum (literally “dip (and) dunk”)* is not a weeknight meal; it’s not an everyday dish; it’s more of a party food which I enjoy no more than twice a year: the day after Thanksgiving and the day after Christmas when palate fatigue from all the cheesy, buttery, creamy, and sweet dishes from the big feast from the day before sets in. Nothing fixes it like a piping hot, brothy meal like this—spicy, sour, salty, herbaceous. It hits all the parts of you that need to be hit. Having most of the friends who live locally around during that time to enjoy it with me makes it even more fun.

It doesn’t mean you can’t have it more often than that.

Recipe? I’m afraid I don’t have one for you. That’s the beauty of hot pot: it’s a free-style meal. True, when it comes to jim jum, there are some essential ingredients that make it what it is, but for the most part anything goes. And the few parts that need special instructions, all long-time readers of this site are already familiar with them.

But let me walk you through the process. Let’s say we’re going to create a jim jum meal for 4 people. Here’s how to do it.

Start with the first component: the broth.

While most jim jum joints in Bangkok I’ve been to use clear broth, many jim jum/jaeo hon joints in Isan tend to use broth that is somewhat murky and sometimes even has a hint of grassy bitterness from the beef bile and the contents of the cow’s intestines. One place in Khon Kaen I remember visiting definitely puts beef blood in their broth which looks almost just as dark as boat noodle broth. If you like those things, go to town. If you, like me, prefer a simple, clear, clean-tasting broth, simply cook up a pot of it using nothing but 5-6 pounds of beef marrow bones and about a gallon of plain water for 4-5 hours, replenishing the water along the way so you have the original amount at the end. You can throw in a couple of cups of cubed daikon during the last 2 hours to add some subtle sweet taste to the broth, but that’s not necessary. Some people don’t like it, but if you like your broth darker with a deeper flavor, you can roast all or half of the marrow bones before using them to make the broth (that’s what I do here).

Once the broth is ready, strain it and pour it into your shabu pot as needed. You can season the broth lightly with salt or fish sauce just so it’s not completely bland. But don’t over-salt it, because the dipping sauce, as you’ll soon see, is pretty salty.

I recommend beef broth, because that’s my top choice when it comes to jim jum. But you can use plain pork broth or chicken broth (there are recipes for them in Simple Thai Food).

You need some herbs. The right ones for the job, that is.

What makes jim jum different from other types of hot pot is the herbs some of which are used in the beginning and some are used as you assemble your meal at the table. I had a conversation over the phone conversation with Chef McDang several months ago when we discussed how many Thai dishes were made following this exact same procedure: some herbs and spices at the beginning and more herbs to perfume the finished dish at the end. Take a simple curry for example. As I’ve explained at length in Simple Thai Food, you always start a coconut-based curry with a paste as the base then you perfume the finished curry again with more fresh herb(s) stirred in at the very end. Chef McDang considers this practice (that is found in every region of Thailand) to be very significant in Thai cooking, and I agree. You see the same thing at work here as well. The strained jim jum broth is infused with galangal, kaffir lime leaves, and lemongrass in the exact same way tom yam broth is. Then you have fresh Thai basil leaves (a must) and culantro or sawtooth coriander (recommended) that you tear up and throw into the simmering broth in small batches along the way for the herbaceous perfume that jim jum aficionados consider absolutely essential. About 4 ounces of each would suffice.

To sum up: Bring your one-gallon broth to a boil; lower the heat so the broth is barely bubbling, throw in 6-7 thin coins of galangal, 7-8 torn and bruised kaffir lime leaves, and 3 lemongrass stalks, cut into 3-inch pieces and smashed with a heavy object until split; infuse for 2-3 minutes then remove them with a slotted spoon and discard. The broth is now ready to be used. The basil and sawtooth coriander can be arranged next to or together with the vegetables as they all are used the same way, though for different purposes, during the meal.

Then we move on to the vegetables.

Anything goes, really, but I would suggest vegetables that are mild in flavor and don’t leach color into the broth (beet is bad). I use napa cabbage, baby bok choy, garland chrysanthemum, water spinach (ong choy), radish sprouts, brown beech mushrooms (buna-shimeji), and enoki mushrooms here. Other good candidates include, though are not limited to, fresh baby corns (I don’t like canned baby corns—sorry; its sour “can smell” ruins the whole thing for me), mild assorted wild mushrooms (shiitake is too strong; I wouldn’t use it), Chinese celery, choy sum, sliced green or Savoy cabbage, curly-leaf spinach, Swiss chard, zucchini, and yellow summer squash.

As a rule of thumb, quick-cooking vegetables, the types that can be softened in simmering broth in seconds, are the best. Aim for one pound of assorted vegetables per person.

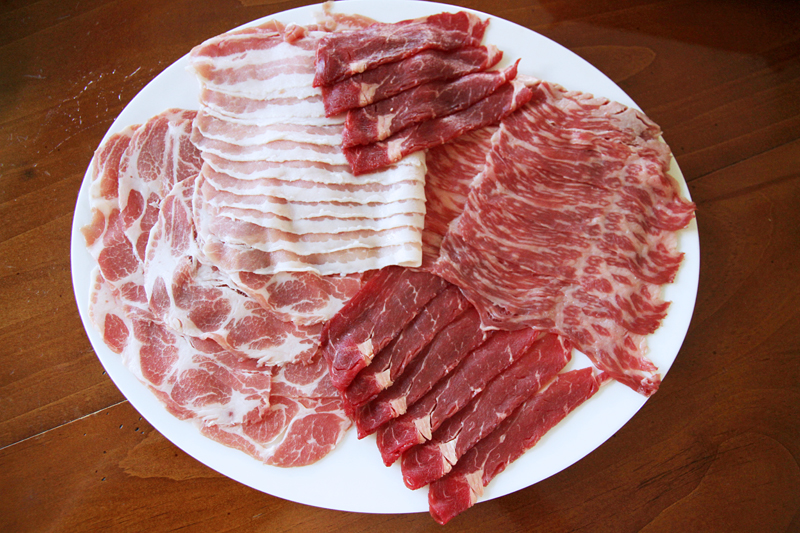

In Thailand, tender, quick-cooking cuts of meat and beef organ meats such as liver, kidney, and bible tripe (omasum) are typical choices for jim jim. You can use anything you like: beef, pork, chicken, etc. Shabu-ready sliced meats from a Japanese or Korean supermarket, which I use here, are a bit spendy, but they will save you a lot of time and energy. You can also use seafood as well, although it’s a little weird to me, because seafood isn’t traditionally associated with the landlocked Isan. If you prepare your own meats, be sure to slice them into bite-size pieces and very thinly. Partially freezing the meat makes it easier to slice.

Many jim jum places marinate their meats with fish sauce and/or soy sauce; some even put beaten eggs into the marinade. You can do so. I leave mine plain, because I like to taste the natural sweetness of the meat. I don’t think we need more salinity here. Plus, the less stuff you add to the mix, the more the gentle perfume of the herbs comes through. But that’s just me who’s definitely in the minority.

Conservatively speaking, one serving of meat is about 3-4 ounces. And if you ask the friends and family who will be eating jim jum with you, they’ll say that as well; they’ll say 6 ounces tops. But if years of hosting jim jum dinners have taught me anything it’s that these people cannot be trusted; they are a bunch of liars whose pants are collectively on fire. Make sure you have at least 1/2 to 3/4 pound of assorted meats per person. In fact, in my experience, the more variety of meats you offer, the more weight they consume per person—sometimes up to a pound apiece.

Then there’s the other stuff, the miscellaneous add-ons.

You don’t really need them. Jim jum is mostly about unprocessed meat, vegetables, and herbs. Unlike a typical shabu or hot pot, you’re not going to find a wide variety of other stuff, like fish balls or seaweed wrapped fish paste. The only thing people, myself included, add to their jim jum set is glass noodles. All you have to do is soaking them in room temperature water just until pliable then cutting them into 4-inch lengths. Placed in a litle wired basket dipped in the simmering broth, the noodles cook in seconds.

You already know how to make jaew (jaeo). You already know how to make toasted rice powder, khao khua, a jaew essential ingredient. So make a double recipe of jaew, mincing the shallots instead of slicing them, and serve it as the dipping sauce for jim jum. For more intense flavor, you can also make a paste of garlic, cilantro roots/stems, and white peppercorns and add it to the sauce. If you go that route, I would say 3 cloves or garlic, 2 cilantro roots (or 1 tablespoon of finely chopped cilantro stems), and 1 teaspoon white peppercorns would be just about right for 2 cups of jaew (double the recipe to which I’ve linked above). To get rid of the raw garlic flavor, you can also boil the sauce gently for a minute and let it cool completely before using.

To make the sauce even more “authentic,” you can also replace half of the fish sauce with the juice from bottled fermented mud fish, pla ra (I’d cook it first, though). Go easy on pla ra, though, if you’re new to this Isan ingredient as it’s a bit of an acquired taste. And since its smell can be off-putting, you may want to hide yo kids, hide yo wife, and hide yo husband when you open a jar of pla ra unless they’re accustomed to and have come to love it as much as the majority of the Thai people do.

All you have to do now is firing up your hot pot burner or a tabletop gas burner. While waiting for the infused broth to a gentle boil, arrange things on large platters and set them on the table around the broth. Everyone gets his own serving bowl along with a small bowl of the dipping sauce and a pair of chopsticks. Then jim and jum away.

The khaen (in the top photo) is optional.

__________________

* Jim jum is sometimes called jaeo hon, especially in Isan. Some will tell you, though, that even though the names jim jum and jaeo hon are often used interchangeably to refer to the same thing, there exist some subtle differences between the two.

Comments are closed.