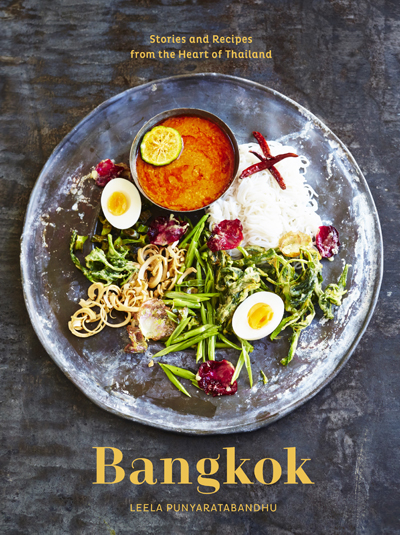

I thought I’d alert your attention to the feature on Bangkok: Recipes and Stories from the Heart of Thailand which TASTE has put on their website; it contains two recipes from the book. I’ll link to the page in a minute. I wanted to make a few remarks about these two recipes first.

The piece contains a brief introduction of the book and two recipes: Preserved Radish Omelet with Crispy Basil and Rice Crackers with Pork-Shrimp-Coconut Dip. Both are great representatives of some of the easier dishes in the Book. I recommend you read this post first before continuing to the actual page on TASTE. Not yet having the book and, therefore, the glossary, you’re going to need this information in order to make the featured recipes.

Preserved Radish Omelet with Crispy Basil

1. The best type of basil to use is holy basil (pictured below). If you can’t find it, Thai sweet basil works too. Don’t have either one? Use the supermarket basil. Fried basil is just an extra touch in this recipe. You can certainly do without it.

2. The radish in “preserved radish” is not this kind of radish but daikon radish which has been preserved and dried. If you’ve been making pad thai along with me for the past several years, you already know hua chai po. It comes in salted/salty variety and sweet variety. The former is—no surprise here—salty with almost no sweet; the latter—a bit misleadingly—is sweetened but also somewhat salty. You will use the sweet variety in this recipe.

Many times these preserved radishes come already minced; this type is great for other dishes, like pad thai (only because it saves you time and energy) but not ideal here (too fine—we’re not going for that texture). There’s also the type that comes julienned/shredded; you can use it. But be sure to use the sweet type and not the salty/salted type. I like to use whole preserved radishes (shown below), because the quality tends to be better (again, be sure to use the sweet type and not the salty type). With the blade of the knife making a 20° angle with the cutting board, slice them crosswise into thin but wide slices, stack up the slices, and cut the stack thinly into matchsticks.

Regardless, don’t forget to rinse the matchsticks as instructed. It may seem silly to wash away the flavor. But different brands have different levels of salt, and it’s best to make the radishes less salty and compensate with added fish sauce—easier to control the saltiness that way.

Oh—and this happens a lot based on the emails I’ve been getting—you don’t want to get preserved radishes confused with preserved cabbage (tang chai). With both preserved radishes and preserved cabbage appearing in Bangkok cookbook, you want to be able to tell them apart in order to avoid using the wrong ingredient.

3. When I say Thai sriracha sauce—whether in this recipe or anywhere at all in the past, present, or future—please know, unless otherwise specified, the kind of sriracha in view is the one the Thai people recognize as sriracha—which means it is not the one with the green cap and a rooster on the label. Look for Shark brand or Sriraja Panich brand from Thailand.

4. Serve the omelet with rice. Like all rice accompaniments, it’s not meant to be eaten by itself.

Rice Crackers with Pork-Shrimp-Coconut Dip

1. This is something that you may have seen on the appetizer menu of old-school restaurants serving traditional Thai food. And the color you’ve seen may look anything from light tan to medium tan with specks of oil in bright orange to dark orange. This has to do with the ratio of the fat (mainly from the pork and coconut cream) and the chiles. But because my family’s recipe calls for fresh river prawn tomalley, the end result will be dark orange (but not hot!) and richer. We love it this way. Prawn tomalley is the pork fat of the river; it makes everything taste good.

2. Speaking of prawn tomalley, if you can’t find it, you can skip it (and the end result will be paler and less rich but it will be good). If you want to make your own substitute (which I do when I’m in Chicago), wait for your book to arrive first week of May (you’ve preordered, right?), because the instructions are in there.

3. Use the correct rice crackers. Finding Asian ingredients using their non-standardized English terms can be frustrating—I know. But the only type you want to use is the kind you see in the photo: crispy rice crackers made from rice kernels that have been cooked and dehydrated. Sometimes they come already fried and ready to use; sometimes they come dried and you will have to deep-fry them yourself. I usually make my own. And I’ve included instructions on how to do that in the book. But if I had to buy, I’d buy the latter as the pre-fried crackers are almost always rancid.

If you can’t find prepared rice crackers and if you don’t want to make your own, the plainest, unsweetened, and the least seasoned variety of this type of rice crisps would work. You just need to account for the extra salt that comes with the commercial rice crisps and adjust the level of salinity of the dip accordingly. Regardless, by no means should you use this type of rice cakes.

4. Make your own tamarind paste according to the instructions in Simple Thai Food or buy a Thai brand of prepared tamarind (like this one or this one). Using a brand, like this one or this one, that isn’t meant for Thai cooking, can ruin your Thai dish beyond salvage. (I’ll write a post explaining why at a later time.)

5. The shallots are supposed to be peeled and finely diced before being added to the recipe.

And that’s it! Let’s move over to TASTE for a sneak peek of Bangkok.

Comments are closed.