(This post assumes that you have read its prerequisite.)

When it comes to Thai restaurants in the West, the one type that brings the widest range of emotions out of me is ran khao kaeng, rice-curry shops.

They’re the ones I hope for (Rotating menu! Variety! New stuff at every visit!), look for (Why are they so hard to find in the US?), get excited about (Hooray! One just opened up in the city!), and am fearful for (I hope they won’t go out of business like the two I’d interviewed in the last 5 years…) the most.

When done right and supported by the members of their community (so the people who run them can continue to do it right), this type of Thai restaurant could become not only the most approachable but also the most variegated and interesting ‘learning center’ for those who want to know more about Thai food and sample a wider variety of Thai dishes.

But the way rice-curry shops operate in the West—and I’ll get into this shortly—can be confusing. Consequently, what’s written about them is sometimes inaccurate. And because I want them to succeed so much, seeing how they’re misrepresented or misunderstood makes me feel nervous for them at times.

In Thailand, the demarcation line between the levels of quality and the prices of the dishes found at a rice-curry shop and those of the same dishes offered at a mid- to high-range, full-service restaurant (like Bangkok-based Krua Apsorn, the Never Ending Summer, Kua Kling Pak Sod, Supanniga Eating Room, the now-defunct White Café, Kalaprapruek, Bo.Lan, Soul Food Mahanakorn, etc.) is clear for all to see and surprises no one. With only a few exceptions, rice-curry shop offerings are typically watered down and made in such a way that allows the operators to maximize profits while keeping the prices low enough for their target customers. If you want well-prepared traditional Thai food made with top-notch ingredients, you go to the latter type of restaurant.

The two types of restaurant are also different in the way they’re set up and run. To compare them, therefore, would be to compare apples with oranges.

In the West, on the other hand, things are a bit murky regarding the role and place of Thai rice-curry shops (a small and emerging sub-genre) in relation to the full-service, menu-based restaurants (which represents the majority of long-standing Thai restaurants in the US). Some nuances are lost in the process of contextualization.

For example, with the price gap being ultra-slim, it’s very difficult to discern the differences between the two that you wonder if they exist any longer. And if these differences, which are clear to see in the context of the Thai eating culture, indeed do not exist in the contextualized version of rice-curry shops in the West, does that mean the only notable difference between them and the regular restaurants lies mainly in the length of time the food sits before it’s served?

Adding to the confusion is the fact that rice-curry shops in the West nearly always expand beyond their purported core competency and end up functioning like a miniaturized version of a mall food court in Bangkok, offering cross-genre foods and services. In other words, they’re a rice-curry shop and also a few other things (such as a boat noodle shop which represents a separate genre all its own). In the Western context, to compare rice-curry shops with other Thai restaurants would be to compare a fruit salad (which contains oranges) with oranges.

Admittedly, this is all bordering on being too simplistic, because it would take many long posts to discuss this subject—which is related to other complex social and cultural issues—more fully. Let’s get to the point.

Imagine you walk into a rice-curry shop at, say, 7:00pm, and are faced with two types of things to choose from, with both costing about the same. One group of dishes have been made in advance and kept warm on the steam table since the morning and will be served to you cafeteria style. The others are to be ordered off the menu, made fresh, and served to you restaurant style. If made-in-advance food is the only thing on offer—which is the case at the majority of establishments that bill themselves as a rice-curry shop in Thailand—then there’s nothing to think about. But in this scenario, what would be the reasons for you to skip the dishes that are made fresh and go for the ones that have been sitting for hours?

Dew Suriyawan, the chef at Chicago’s only rice-curry shop, Immm Rice & Beyond, can think of one.

“Curries that have been sitting for a while taste better than curries that are made fresh,” he insists. This is the branding message that he (above, left) and his partner, Noon Tosakulwong (above, right), have been sending out to the people of Chicago regarding why their steam table offerings represent the strength and uniqueness of their rice-curry shop and showcase Thai dishes as they’re supposed to be. “We’re trying to keep our food as close as possible to how it is in Thailand.”

Ordinarily, I would disagree that rice-curry shop offerings are better or more ‘authentic’ or a truer representation of the Thai eating culture than what you’d find at other types of restaurant. I would also disagree that rice-curry shop offerings are superior to restaurant offerings solely by virtue of them being made in advance and having had time to “age” and develop deeper flavor. As we know, despite its name, a rice-curry shop offers much more than curries. And I’m not convinced that things like bean sprout stir-fry with tofu (phat thua ngok kap tao hu) or deep-fried fish (pla thot), which you often find among rice-curry shop offerings, taste better the longer they sit. The quality of most salads (yam), which—you’ll recall—are served with rice, only deteriorates the moment they leave the tossing bowl.

However, specifically in the case of Immm (a dramatized romanization of the Thai word อิ่ม, im, which means “full” or “sated” or even “satisfied”), Dew’s bold assertion is valid. This is because:

1. He speaks only of curries, and Thai curries do taste better when they have time to sit in the warming mode—or at room temperature—for as long as they can without reaching the point of spoilage. Refrigerating and reheating them again and again (better on the stove top than in the microwave) also do the trick. Have you had a classic beef green curry with Thai round eggplants (recipe in Simple Thai Food) that’s reheated so many times it turns thick with the eggplants unphotogenically disintegrating into the sauce? Try serving it hot on top of room temperature (or even slightly cold) jasmine rice and experience how something so hideous it scares little children—and probably your pet rabbit—can taste oh so good.

2. Immm’s steam table focuses heavily on curries and braised dishes. Apart from the usual suspects, you’d find here some lesser known (which really should be more widely known) dishes, such as kaeng tai pla, the iconic southern coconutless curry of mixed vegetables and fish featuring fermented saltwater fish innards, or pla ra song khrueang, the creamy curry-like relish comprising mixed vegetables and fermented freshwater fish. These are dishes that deepen in flavor and become noticeably tastier when left to sit for hours.

So, yes, based on the indiscernible differences between the two types of restaurant in the West as mentioned above, based on what we know about curries, and based on the fact that curries make up the majority of Immm’s steam-table selections, Dew is right in saying that his rice-curry shop offerings are better than their counterparts at a typical menu-based restaurant in the US.

Immm offers several curries. But the one I always get when I go there is kaeng the-pho (แกงเทโพ), pronounced gaeng tay poh, which is different from the other well-known Thai curries found at most Thai restaurants outside Thailand. It’s an old curry which has been around for at least a century, with its prototype made with the-pho (hence the name), a highly prized fatty fish which is very hard to find these days. The version of kaeng the-pho served at Immm is the modern-day street version, the same one you’d find at any rice-curry shop that offers it. Instead of fish, this version features pork belly.

The curry looks uncomplicated, but it’s not the easiest to make well. The seasoning part is challenging. For green or red curry, there’s no sour flavor involved at all (by the way, will the Internet please stop squeezing lime into green curry?); they’re mainly salty with the faint sweetness from the natural coconut or a tiny, tiny bit of added palm sugar. So that’s not much of a challenge. In the case of kaeng the-pho, however, you get to harmonize the three flavors: sweet, sour, and salty with the first two more forward than the last. We’re talking about a territory even experienced Thai cooks fear to tread.

But practice will get you there.

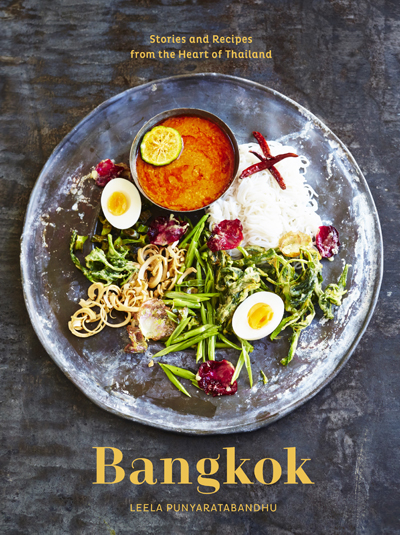

One of the essential and defining ingredients of kaeng the-pho is water spinach, also known as Chinese water morning glory. The cultivar traditionally (I wanted to say ‘solely’ because I’ve never seen any other cultivar used in this curry, but let’s play it safe) used to make this curry is what the Thai call phak bung thai (Siamese water spinach) which also goes by the name of phak bung kaew (above, right). This type of water spinach isn’t found in the US. On this side of the Chao Phraya, the only type that’s available is ong choi (you’ve seen it before) or what the Thai call phak bung jin or Chinese water spinach (above, left). Siamese water spinach is grown in water (sometimes in swampy soil); the latter is grown in soil. The former has wider, crunchier, and juicier stems that withstand longer cooking time quite well; they absorb and retain the seasoning more readily; they turn tender and soft, instead of stringy, if overcooked. Chinese water spinach, on the other hand, has thinner but tougher stems that are less crunchy and juicy. It performs best when flash-fried or cooked very briefly. If cooked beyond the point where it’s tender-crisp, it will instantly turn into a pile of thick, green, vegetal pieces of dental floss—especially when the stems are very slender (like what you see in the cover photo at the very top).

If you live in the US, you’re going to have to use Chinese water spinach—which is fine. Immm and everyone else does too. Just be careful not to overcook it.

Also essential to the modern-day version of this curry is makrut or kaffir lime. Its purpose is not to provide the sour flavor but to lend its unique fragrance that’s come to be an important feature of this curry.

“A little goes a long way,” says Dew. “You don’t want to add too much of it or let the lime half stay for too long in the curry because it will turn everything bitter.” Wise words.

If you live in Bangkok or visit the city often, look for kaeng the-pho at a rice-curry shop near you (because it’s unlikely you’ll find it at a restaurant). It’s usually kept in a large pot; you can’t miss it. Otherwise, endear a Thai friend hoping he or she will invite you over to his/her house for dinner and serve you this quintessential homestyle dish.

If you live outside Thailand, you can follow the simplified recipe for kaeng the-pho below, courtesy of Dew Suriyawan of Immm Rice & Beyond in Chicago, to experience this lesser known Thai curry. And if you live in or visit Chicago, go to Immm to enjoy this curry and many more—after they have been sitting on the steam table for a while, that is.

- ½ teaspoon cumin seeds

- ¼ teaspoon cardamom seeds

- 3 dried red Thai long chilies (or guajillo chiles), stemmed, deseeded, cut into 1-inch pieces, soaked in warm water until soft, and squeezed dry

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 teaspoon packed Thai shrimp paste

- 1 tablespoon paper-thin slices lemongrass (from the bulbous part close to the root)

- 1 4-ounce (114g) Maesri kang kua curry paste

- 2 tablespoons finely diced shallots

- 4 large cloves garlic, peeled

- 2 tablespoons vegetable oil

- 1 pound boneless pork belly, cut into ½-inch-thick slices and cut each slices crosswise 1½ inches wide

- 1 14-ounce can coconut milk

- 2 tablespoons fish sauce

- 3 tablespoons prepared tamarind paste (made with 340g block of seedless tamarind pulp and 1 quart water)

- 1 ounce grated palm sugar

- 2 ounce (weight after trimmed off roots and though parts of stalks) water spinach (ong choy/choi or Chinese water morning glory), cut crosswise 2 1//2 inches long

- One half (cut crosswise) of makrut lime (Omit if you can't find it. Do not use regular lime.)

- Toast the cumin and cardamom seeds in a dry skillet over low heat until fragrant, about 2 minutes; transfer to a granite mortar.

- One at a time, add the chilies, salt, shrimp paste, lemongrass, curry paste, shallots and garlic; grind until smooth after each addition.

- Put the paste with the vegetable oil in a large wok or Dutch oven over medium-high heat until fragrance, about 1-2 minutes.

- Add the pork belly and stir just until the pork looks taut on the outside. Add the coconut milk, fish sauce, tamarind, and palm sugar; bring the mixture to a boil, cover, and simmer on medium until the pork is tender with some bite to it, about 20-25 minutes.

- Taste the sauce. Adjust the seasoning as needed with more fish sauce, tamarind, and sugar to achieve the three flavors of sweet, sour, and salty.

- Stir in the water spinach and the lime half. Push it all down with a spatula; add more water, if necessary to get everything submerged. Turn up the heat to high to bring the mixture back to a boil. Once it boils, turn off the heat immediately and let the residual heat cook the water spinach. Let the curry stand 30 minutes so the lime infuses the sauce. Remove and discard the lime after that. Serve with rice. But if you can wait, let it sit for at least 4-5 hours (in an air-conditioned kitchen) or let it cool completely then refrigerate it overnight and eat it the next day.

Comments are closed.