Portrait by Vichai Kiatamornwong

Breathlessly, I sat there with my pupils amply dilated as

M.L.

[1] Sirichalerm Svasti, better known as

Chef McDang, regaled me with stories of what a typical meal time was like at Sukhothai Palace. Sure, you can find secondary, tertiary,

quadriary accounts anywhere about dining in the palace by those who know — or think they know — about the subject. But, you see, I was listening to a first-hand witness who spent more than a decade of his youth at the scene. And in many ways it is as if I was in the presence of an extant papyrus manuscript detailing historical events. The exception, of course, is that this manuscript is interactive.

Suddenly, I was reduced to a wide-eyed little girl sitting cross-legged — a fluffy stuffed animal in her tight embrace — listening attentively to a story of the enchanted castle.

Dinner at the Palace

“A typical dinner lasted about two and a half hours,” said Chef McDang. My eyes grew cartoonishly bigger by the minute as he reminisced the dinner scene presided over by his great-aunt, Queen Rambhai Barni. The meal, said the queen’s nephew, started off with soups and appetizers, and was followed by the main course all of which were delivered daily from Chitralada Palace kitchen per His Majesty the King’s gracious directive. This Western meal was served Russian style[2] with butlers presenting food on silver platters to the Queen first before moving on to the other people at the royal table.

Wait a second. Western meal? Served Russian style?

“You have to remember that the palace represents the center of government and first contact point to the outside world,” said Chef McDang. “New western or foreign influenced dishes usually originate from the palace.”

There goes the myth about the palace being the place to look for ironclad authenticity in terms of cuisine or about the royal cuisine being a separate class of its own (more on that in this CNNGo article).

Of course, traditional Thai food was part of the royal dinner. Once the western meal was finished, the Thai meal commenced. The whole samrap (สำรับ), an entire ensemble of various dishes for the whole meal, was set separately for Her Majesty. The gap khao (กับข้าว) — the dishes to be eaten with rice — he recounted, were never placed on the same plate with or on top of the rice (as done by street vendors). The dishes served were regular Thai fares put together to form a varied yet balanced Thai samrap that consists of a clear soup, a curry, a stir-fry item, a deep fried item, a salad, and an indispensable nam prik (chili relish) with all its accompaniments.

“The rest of us were served Russian style. The table would be reset for each one of us with a plate for rice and a half moon-shaped plate to the left of the the rice plate for all the various dishes.” And if there were soups or curries, said the chef, they would be served individually in small bowls with ceramic soup spoons. “The butlers were the ones serving you the rice and you could just glance at them for more rice and more gap khao and they would bring them to you,” he said.

And I sighed. With me growing up on the wrong side of the palace wall, my glances — even my stares regardless of how intense and meaningful they were — fell on whomever was around the dinner table like a bunch of dud grenades.

But I digress.

Portrait by Vichai Kiatamornwong

After the completion of the savory meal, the table would be reset first for Western desserts then fresh fruits, followed by traditional Thai desserts. As usual, the Queen would have her own

samrap of fruits and desserts while the other people, McDang included, were served Russian style.

Asked which dish served at the palace he liked the most, Chef McDang recalled how much he loved the quintessential summer dish, Khao Chae (ข้าวแช่), the dish that is traditionally served during the dry and hot season to cool you down. I could hardly hide the grin on my face for, you see, finally — something we have in common.

To make Khao Chae, inside or outside of the palace, rice in jasmine-scented iced water is carefully prepared and served with assorted savory delicacies. Most Khao Chae ensembles in the various palaces in the olden days consisted of the usual accompaniments which were more elaborate in the way they were prepared. Take one of the most popular Khao Chae accompaniments, stuffed banana peppers in wispy egg shrouds, for example. “Some palace cooks would steam the stuffed peppers first before deep-frying them and wrapping them in the egg threads,” said Mcdang.

Everything else was also meticulously prepared. Vegetables would be peeled, cut into bite-sized pieces and beautifully carved. Fruits would receive a similar treatment. No pits, seeds, peels, or stones would be found on the fruit platter. Yet, in terms of the food itself, what was served at Sukhothai Palace is the same as what you would find anywhere in Thailand.

“Most people think that royal cuisine is different from regular Thai cuisine and that there is something very grand and magical about it,” said Mcdang. That couldn’t be further from the truth. “The myth that royal Thai cuisine is different than regular Thai food is created by the marketing minds who wanted to charge more money for Thai food,” he added. What makes palace food special lies in the fact that the cooks in the olden days used the best raw materials and took great care in making sure that the food tasted balanced and there were no extremes in flavors. That is to say, the food wouldn’t be too salty, too sweet, too sour, or too hot.

There’s a bit of a surprise, however.

“I remember the Queen even had her own rice steamed in an earthenware crock and it was red rice,” recalled Chef McDang. With that, the oft-repeated theory of the unpolished red rice being consumed exclusively by citizens of the lowest class and the more refined white jasmine rice being reserved for those belonging to the upper crust of the society is crushed along with the notion of the royal cuisine being different from the regular Thai cuisine.

Authentic Thai Food

“Authentic” is a word that we all have used without being able to clearly define. I still haven’t been able to grasp just what “authentic” means, and my quest for clarity has not been very fruitful.

When it comes to cuisine, “authenticity” is to me a word that is — at a risk of sounding intoxicated — both loaded with meaning and meaningless at the same time, depending on how you look at it.

Recently, attempts, it seems, have been made to convince the public that the myriad of dishes found in modern Thai cuisine are corrupted, that the Thai cuisine is in decline and in need of a rescue. It has been intimated that one needs to duplicate the cuisine of a specific era (namely the era after the printing press had been introduced in Thailand during which written records of the making of traditional Thai dishes emerged) in order to experience “authentic” Thai food. Collections of old recipes based on extant written records, therefore, have been presented as ‘authentic.’

While there’s nothing harmful in that, Chef McDang dismisses the methodology of such undertakings as misguided.

A mortar and a pestle – the most important tools in Thai cooking.

To truly understand what Thai food really is about, one needs to adopt a bird’s eye view of the entire span of known Thai history and capture the elements which form a theme that runs diachronically. That theme is the framework of Thai cuisine which, in turn, defines it.

According to McDang, the key to comprehending what authentic Thai cuisine is lies in an understanding of the rules and regulations that govern Thai cooking. “There are basic do’s and don’ts in Thai cookery which most Thais don’t even know or bother to try to understand,” the ever-so-candid chef said. “They take Thai food for granted.”

Oh, how many times have I heard that in recent weeks?

There are two major rules and one exception to authentic, traditional Thai cooking according to McDang’s theory.

- Salinity is derived from fish sauce; sweetness from palm or coconut sugar; sourness from locally-available tropical fruits, e.g. tamarind, green mango, lime. The use of soy sauce for salinity or vinegar for acidity is all a result of late foreign influence.

- One cannot cook Thai food without making a kreung tam (เครื่องตำ) or a paste regardless of the cooking technique. Just as the French have their grandes sauces or sauces mères (mother sauces), the Thai have our pastes upon which various dishes are built.

- The exception to the rule is when you make a soup that is an infusion (which is akin to making tea). Tom Yam, Tom Kha Gai, etc., all fall into this category of pasteless dishes.

The cooking techniques found in Thai cuisine are quite simple, McDang has pointed out. The most basic and prevalent technique is grilling. This explains why there are so many Thai words for different types of grilling. Also, since the beginning of time Thais have only had clay pots to cook with. It was not until the beginning of the Rattanakosin Period, when the presence of Chinese immigrants became more prominent, that we started to cook with a wok which is essential for stir-frying and deep-frying.

Over the ages, Thai cuisine has undergone changes along with the changes in social milieu. Yet, we can see how the aforementioned two rules have continued to govern the way in which Thai food is traditionally made. We can also see how the flavor profile remains the same. We’ve borrowed extensively from our foreign neighbors and visitors, but we have continued to operate within the same framework. The players may change or grow in number; the rules remain unchanged.

In other words, according to McDang, authenticity has nothing to do with antiquity but everything to do with the governing principles which are transcendent and timeless. In light of this, we don’t need to stay stuck in a certain era or regard the dishes prevalent in that era as the prototypes of Thai dishes.

“There is a definitive Thai cuisine if you know these rules and stick by them,” said McDang. “This is important for most Thai cooks to understand because if they do, they will be able to create new Thai dishes based on the governing principles.” The structure provides a solid framework within which imagination and creativity operate. Modern Thai dishes can be created, even with ingredients from other parts of the world, and they will still continue to manifest the profile of Thai cuisine.

The Principles of Thai Cookery

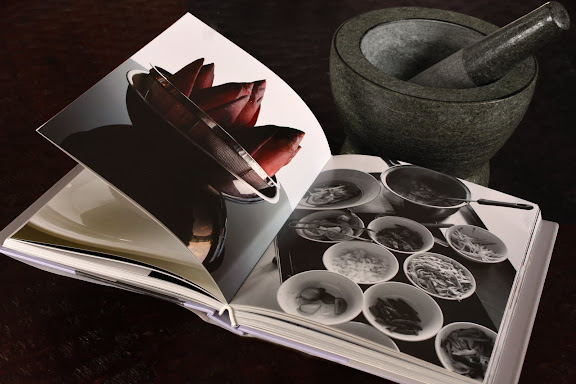

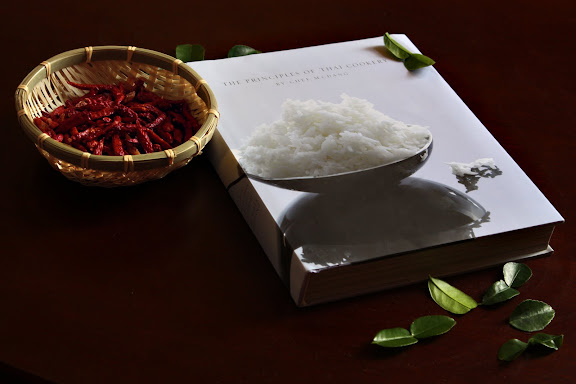

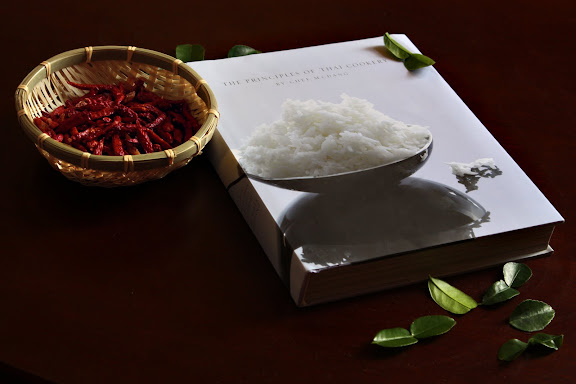

In The Principles of Thai Cookery, McDang’s first English-language book, the chef has explained his theory on the fundamental elements of Thai cuisine in a much more lucid and plenary manner. This self-published book, which has recently made JP Morgan’s reading list, represents a long overdue “textbook” on Thai cuisine that Chef McDang had spent years writing.

The Principles of Thai Cookery

It needs to be said that

The Principles of Thai Cookery is

not your typical cookbook. It is unlike any other book on Thai cuisine in that it is not prefaced by

everything there is to know about the history and geography of Thailand, a well-worn strategy to establish credibility (often at the expense of relevance and bordering on over-compensation). Neither is it a collection of

every recipe available in print

physically bound together —

pertinence be darned — to form a gigantic concordance.

The Principles of Thai Cookery is a fluff-free book containing only pertinent material arranged thematically with a framework securely in place. Insights into the food history, the culture, and the Thai way of eating take the place of gratuitous information.

Chef McDang, a graduate of Culinary Institute of America, is a strong advocate of teaching Thai cooking through science and the kind of pedagogy employed in premier culinary institutions worldwide. Cooking is not a mysterious, cultic thing that is to be passed on through rote memorization of ingredients and procedural steps; cooking is science and, therefore, should be explained accordingly. The Principles of Thai Cookery is arranged according to cooking techniques. If you see this book as a cookbook, this may seem rather strange. But when you take into consideration that this book that contains nearly 60 essential Thai recipes is first and foremost a textbook, such organizing principles make sense.

I like this book. A lot. And I recommend it wholeheartedly to any Thai food lover or anyone who wants to understand the basic tenets of Thai cuisine.

Cooking is Science

I asked McDang which recipe in The Principles of Thai Cookery was his top favorite and he was sort of rolling his eyes at which point I realized I’d foolishly asked someone to identify which of his kids was his favorite.

A stubborn negotiator, I refused to back down. Finally, I succeeded at irritating him into telling me which of these 57 recipes was the most interesting dish to feature with this article. “Hor Mok,” [3] the chef made his pick.

Why? It represents a dish that is not Thai in origin, but has been adapted to fit into the framework of Thai cuisine in such a way that we now have a dish that is decidedly and uniquely Thai in terms of flavor profile even though the influences of the Indian, the Moor, and the Portuguese are undeniable.

Something about the name, Hor Mok, sent chills down my spine. No, I don’t hate the dish; I love it. I was just reminded of those days when my paternal grandmother would make me grate coconut with the coconut rabbit while she scraped the flesh of fresh chitala chitala (ปลากราย) off its spine bones in the process of making Hor Mok. One of my aunts would be pounding the curry paste. Once I was done with the coconut, she would extract the coconut cream out of it. And, oh, boy, did I ever know what would happen once I dismounted the bunny.

The fish meat would go into a clay pot along with the pounded paste, some duck eggs, and coconut cream. And sulkily I would sit there — pot in lap — and stir the fish mixture counter-clockwise until my right arm was just about falling off. The fish mixture would get fluffier and more viscous towards the end while my resentment grew. But it was necessary, said Grandma. Unfortunately, she left it at that. Without the explanation, all that stirring felt to me like a cultic ritual performed to appease a kitchen god.

But, no, it’s all about science.

Hor Mok is nothing but Western-style fish mousse flavored with curry paste[4] and thickened with coconut cream as opposed to cream. Also, instead of being formed into quenelles and poached, the curried fish mixture is steamed in banana leaf cups or packets.

What about the whole stirring stuff in the clay pot business? That’d better serve some lofty purposes, because — let it be known — at least a quarter of my childhood was spent with a clay pot in my lap while I stirred my life away.

“When you make fish mousse, everything must be kept cold,” said Chef McDang. “This prevents the protein in the fish from stretching and creating an unpleasant, grainy texture.” That makes sense. A clay pot is probably the only thing that would do the trick in the pre-refrigeration days.

Grandma, are you reading this?

_______________________

I’d like to express my heartfelt thanks to M.L. Sirichalerm Svasti for graciously granting me the interview. I am a grateful recipient of the knowledge imparted through his book, email messages, and a lengthy conversation. Despite his privileged upbringing, Chef McDang exhibits no trace of arrogance. Not only is he approachable, he’s also funny as heck. The interview with him is by far one of the most — if not

the most — entertaining interviews I’ve ever conducted with anyone. There were moments when I learned new things, moments when I was corrected in my thinking, and moments when the chef made me laugh so hard apple juice came out of my nose. For all of those moments, I thank him.

Disclosure: SheSimmers.com is not in any way related to ChefMcDang.com. The positive review of The Principles of Thai Cookery has not been motivated by any kind of compensation, monetary or otherwise.

Hor Mok (ห่อหมก) - Thai Curried Fish Custard and The Principles of Thai Cookery by Chef McDang

Author: ML Sirichalerm Svasti

Recipe type: Main Dish, Entree

- 2½ tablespoons store-bought red curry paste, cold

- 500 g boneless, skinless white-fleshed meat, cubed (cold)

- 1 egg, cold

- 2 cups coconut cream, cold

- 1-2 teaspoons palm sugar

- 3 tablespoons fish sauce

- 1 cup Thai sweet basil leaves

- 1 cup coconut cream (for topping)

- 2 teaspoons rice flour (for topping)

- 5 kaffir lime leaves, finely julienned (half for garnish)

- 2 large red chili peppers, deseeded and julienned (for garnish)

- Prepared banana leaf cups for the fish custard (ramekins or any container that will hold the mousse during steaming will be a fine substitute)

- Place half of the fish cubes, the egg, curry paste, palm sugar and fish sauce into the work bowl of a food processor. Turn on the food processor and let it rip (remember that everything has to be cold).

- Once the fish starts to ball up, add the cold coconut cream while the machine is still running. This will create a creamy mousse and the consistency can be controlled by the amount of cream you add – it’s just a personal preference.

- Taste the mousse. It should be salty, slightly sweet and creamy. If you prefer not to taste it raw, fry a dollop of the mixture in a non-stick pan, then taste. Adjust seasoning according to your preference.

- Add half the julienned kaffir lime leaves to the mixture and blend further.

- Distribute the Thai sweet basil leaves evenly along the bottom of each banana leaf cup. Place the remaining fish cubes on top of the sweet basil, then fill each cup with the prepared mousse.

- Heat one cup of coconut cream with the rice flour in a saucepan until it thickens. Spoon over the contents of each cup and garnish with the rest of the kaffir lime leaves and the julienned red chili peppers.

- Place cups in the steamer and steam until done (usually ten minutes).

- Serve either hot or at room temperature with rice.

2.2.8

[1] Short for Mom Luang (หม่อมหลวง)

[2] During a Russian-style banquet, trays are presented to each guest and they serve themselves from the trays.

[3] Also spelled Ho Mok or Haw Mok. Personally, I’m not a fan of using the letter “r” as a mater lectionis, but Hor Mok is by far the most prevalent spelling and, therefore, used here, albeit reluctantly.

[4] In the old days, wild-caught fresh-water fish had unpleasant smell to them and a paste of fresh herbs and spices would be the only way to counteract that muddy smell.