Choosing where to eat in Bangkok is never easy; we’re talking about a big and diverse city, teeming with choices. But if forced to identify only one segment where I think the city’s best food is found, I would point to the homes—specifically the homes of old families who cook from recipes passed down for generations. A close second would be restaurants that serve traditional Thai dishes based on family heirloom recipes.

I never understand—or like—the whole unless-it’s-found-on-the-streets-it’s-not-good-or-authentic sentiment, which I’ve noticed from time to time in travel writing or travelers’ comments about Thailand, especially Bangkok. It doesn’t reflect the reality of how Bangkokians actually eat or the way they see their own food. It’s objectively wrong. It minimizes the importance and contribution of the restaurants in the city many of which seek to preserve local traditions and support responsible farming as well as small-scale artisans. It’s like fingernails on a chalkboard to me. And I find it just as irritating as the assertion that royal Thai cuisine is the only authentic Thai cuisine.

There’s nothing wrong with being excited about street food or even loving it to the exclusion of others. I, too, love street food. It’s fun; it’s convenient. The streets are where you’ll find lots of things that even the most able and dedicated home cook won’t/can’t make at home. But when that excitement turns into blind, broad-stroke deification of cheap street food and disparagement of more refined establishments, it becomes problematic.

When it comes to traditional Thai cooking, home cuisine rules the roost. That’s where it all began; that’s where the foundation lies. The sight of an abundant and colorful spread of curries, stir-fries, and other rice accompaniments on a rice-curry shop’s steam table may be exciting to visitors to Bangkok. But what is a rice-curry shop but something that exists more for convenience than anything else? What is a rice-curry shop if not a home kitchen wannabe that could hardly be? All good rice-curry shops in or near Bangkok—Nat Phop in Nonthaburi, for example—are lauded for what, if not how well they mimic the old-school, home-style dishes? (The same scenario applies to catering services; we’ve seen some examples of that.)

The only way to truly see that there’s more to a cuisine than what’s out there on the streets is to be in a home where people cook. Understandably, that’s a privilege most international travelers don’t get to enjoy. When I travel to a different country, I often find myself in the same situation.

Before I came to the States as a student, I’d read enough American cookbooks and food magazines to get a pretty good idea of what American cuisine was all about. But on a personal level, no amount of reading had ever opened up the world of American regional cuisines, city-specific cuisines, or home cooking to me nearly as effectively as being invited by my American friends to their homes in various cities and states.

By having me over (for a weeknight meal, a holiday meal, or a church or synagogue potluck), those kind families had allowed me to enter their private world and learn a great deal the things I wouldn’t have learned otherwise. With my limited student’s budget, what would have been the scope of my exposure to the food of America—at least in those early years—without these people? Cafeteria food mostly. Fast-food joints. Chain restaurants when I had some extra money.

In my limited knowledge (but ample sincerity), I could have concluded that the best of American cuisine—the most authentic American food—could be found at McDonald’s, KFC, White Castle, or Subway—perhaps Applebee’s, Olive Garden, T.G.I Friday’s, or The Cheesecake Factory for something a little fancier but still “real.” After all, what I found at these places was far superior to the bogus “American” food made by some local restaurants in Bangkok I used to eat before I came to the US. I could have told anyone who would listen that if they ever go to America, be sure to eat only at those places to experience the true glory of American cuisine.

This is the kind of thing that is written about Bangkok far more often than you think.

I’m digressing. What I’d like to say is that there’s a home in Bangkok that opens its door to everyone, locals and visitors, and that you should go eat there.

The folks at Baan Varnakovida (pronounced bān wannakōwit, Thai for the house of the Varnakovida family) have recently turned their home in the historic area on the Rattanakosin Island of Bangkok into a small and intimate restaurant. There, you’ll sit in the dining room of their century-old home and get just about as close as you could get to eating like a true blue Bangkokian who grew up on this kind of middlebrow, traditional home cooking. You’ll get to enjoy dishes that have been made for generations. You don’t get this kind of experience on the streets. Or at the shophouse eateries. Not even at the lushest of fresh markets. You may get a glimpse of what that world is like at some of the restaurants in the city. But here you’ll get to sit right in the middle of it.

Khao chae is one of the featured dishes at Baan Varnakovida, and it’s something you should try. This dish comprises a bowl of rice in iced, flower-scented water which comes with savory sides specifically designed to accompany the rice. This is something you’ll hardly find on the streets (even some people who have lived in Bangkok for years and decades aren’t familiar with it). And if you do, it usually comes in a heavily-simplified, stripped-down form. During the summer months in Bangkok, this cold, refreshing classic pops up more at some hotel lunch buffets and sit-down restaurants as a seasonal, limited-time special. But at Baan Varnakovida, you can have it all year round. Don’t worry if you’re not familiar with the khao chae etiquette (and there is such a thing), Apavinee Indaransi, the family member who runs the kitchen, will be there to explain it all to you.

Apavinee had long wanted to quit her office job. After many years, the commute had become unbearable. What prompted her to finally bite the bullet and do so was Bangkok’s last major flooding in 2011. That, and her mother’s sudden need for a caretaker.

“But after having stayed home a while I got a bit restless,” said Apavinee. “The house felt lifeless and there was a void there, and I wanted to do something both to revive this old place and to create meaning in my own life.”

Though she hardly cooked before, Apavinee got into the kitchen and reacquainted herself with the dishes she’d grown up eating. The family has a pretty extensive repertoire of home-style dishes, but Apavinee focused on khao chae, the crown jewel of them all. Soon friends started ordering khao chae sets from her through Facebook. And the more she cooked, the more she realized this was something she could do that would both create the meaning she sought and provide her with a steady income. With that, Baan Varnakovida as a restaurant was born.

The 2-storey house was built in the reign of King Vajiravudh, the sixth king of the House of Chakri, and sits on the half-acre lot the monarch had bestowed on Apavinee’s great-grandfather Luang Varnakovida (Krachang Varnakovida) who served as a royal chancellor. The wooden house features the so-called gingerbread architecture which was the style of those days. It also has a basement which the family used as the bomb shelter when Bangkok was at the receiving end of frequent aerial bombings by the Allied forces during the Asia-Pacific War. The house, these days, is a cozy, quiet place, surrounded by fruit trees the most fertile of which are the sapodilla plants (shown above). There’s nothing about it that would tell you it’s a restaurant. When you arrive, you will have to be let in through the front gate as if you were a house guest. Around 60-80 people have come through this gate on a daily basis since late 2014—all by word of mouth, without any advertisement beyond social media.

“People have been talking me into turning the place into a full-fledged restaurant,” said Apavinee. “They’ve been suggesting to me ways to mass-produce food more efficiently, but I don’t want that—I want to keep it small and intimate.”

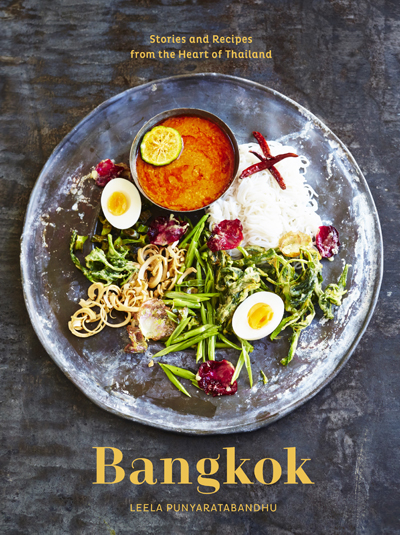

And so—at least for now—everything is still made in small batches by hand with no industrial equipment. Every morning Apavinee makes a trip to the market at Pak Khlong Talat, the famous Flower Market on the east bank of the Chao Phraya, and gathers all the fresh ingredients for the day. The scenting flowers (jasmine flowers, rice flowers, ylang-ylang, roses, etc.), essential to the making of khao chae, still come from the family’s unsprayed garden. The menu is also kept small intentionally. Other than khao chae, there are only a few other classic home-style dishes such as rice crackers with savory coconut dip (khao tang na tang), pineapple canapés with sweet pork-peanut topping (ma ho, see my recipe in Simple Thai Food), and rice vermicelli topped with coconut sauce and fish dumplings (khanom jin sao nam). Apavinee also offers her own twist of the classic watermelon with salty-sweet fish dip (pla haeng-taeng mo), using deep-fried tiny shrimp instead of the traditional dried fish flakes.

In case you’re wondering, yes, you want to try everything.

As a gift to my readers, Apavinee has shared with SheSimmers one of her family’s heirloom recipes, caramel-glazed pork cracklings and peanuts (kak mu-thua wan), which is something I’d never heard of until now. Crunchy, freshly-made pork cracklings and fried peanuts (I use toasted peanuts here) are coated in light caramel that’s made of fish sauce and palm sugar (I use a combination of palm sugar and dark brown sugar, because Thai palm sugar exported to the US doesn’t pack enough flavor). The caramel is supposed to remain soft and sticky and not hard and brittle even when the dish has cooled down. To achieve this, Apavinee uses glucose syrup, generally referred to as bae sae in Thailand. But you can use corn syrup (not to be confused with high-fructose corn syrup), tapioca syrup, brown rice syrup, or honey; none of this works as well as glucose syrup, but it will do. If the caramel hardens upon cooling, simply stir in a tiny amount of hot water to loosen it up a bit and you’ll be good to go.

The result is a rich, sweet and salty dish that’s best enjoyed with warm rice sparingly—almost as a condiment—alongside other dishes in the same meal ensemble—ideally something light, tart, and vibrant or something fiery (I recommend southern sour curry with pineapple and shrimp, southern pork rib curry, or scallop-orange-cucumber salad.

Baan Varnakovida is located at 64 Thanon Tanao, Wat Bowon Niwet, Phra Nakhon, Bangkok 10200. It opens daily, except for Thursdays, from 11:00am to 4:00pm. Walk-ins are welcome, but it’s best to call Apavinee at (0)819226611 for reservations.

- 1 pound pork fat

- 3 cups water

- ⅔ cup unsalted dry-roasted peanuts

- 2 tablespoons packed palm sugar

- 1 tablespoon packed dark brown sugar

- 1 tablespoon corn syrup (not high-fructose corn syrup) or tapioca syrup or brown rice syrup or honey

- 1 tablespoon fish sauce

- ¼ teaspoon ground white or black pepper

- Cut the pork fat into ¾ inch by ¾ inch squares and put in a 10-inch skillet or a 2-quart saucepan along with the water; bring to a boil over high heat. Lower the heat to medium and cook, stirring often, until the water has evaporated leaving the pork fat chunks in white, greasy, cloudy liquid.

- Turn the heat down to medium-low and cook, stirring often, until the pork fat has shrunk, crisped up, and turned golden brown.

- Strain to separate the lard from the cracklings. Set the cracklings aside. Reserve 1 tablespoon of the lard; store the rest to use for other purposes.

- Put the peanuts in a 8- or 10-inch frying pan or skillet and place over medium heat. Toast, stirring almost constantly, until light brown, about 8-10 minutes. Immediately transfer to a heatproof plate. Don't turn off the burner yet; keep it on medium heat.

- Wipe the pan clean and put it back on the burner. Add the reserved 1 tablespoon of lard, palm sugar, dark brown sugar, corn syrup, fish sauce, and pepper; boil hard for 1 minute.

- Add in the pork cracklings, the toasted peanuts, and a tablespoon of water; stir to coat.

- Plate and serve at room temperature with rice along with other rice accompaniments.

[…] Source: Caramel-Glazed Pork Cracklings and Peanuts […]