A familiar sight when I was a kid growing up in Bangkok was that of someone on a bike going around the neighborhood to deliver food packed in a container called “pinto.” And though our family never used this daily catering and food delivery service, we were familiar with how it worked. How could we not? Advertising pamphlets were put in our mailbox every week, tempting us with the prospect of having a home-style, multi-dish meal delivered fresh to our door every day. A full samrap on your dinner table without you having to lift a finger? I’m pretty sure that even though my mother never actually signed up for the service, she must have toyed with the idea from time to time, especially on days when work became too demanding.

A weekly menu would be published and delivered to your mailbox at the beginning of the week or the month. The menu, rotating from week to week, would depend heavily on seasonality. A typical ensemble would include a soup, a stir-fry, a curry, a fried dish, and a dip or relish with fresh vegetables. Most pinto operators would offer multiple choices in each category for you to choose from which means you’d have a certain amount of freedom to customize your samrap to your liking. Each dish would then be packed into a single container, then all of the containers would come to you stacked on top of one another and secured into a single unit by a metal frame. Once you’re done with your meal, you clean the pinto and leave it outside your house gate to be collected by the delivery person who would come by again the following day to deliver another fresh pinto.

With Bangkok restaurants and shops being so good and efficient with food delivery via motorcycle dispatchers these days (did you know even American fast-food joints like McDonald’s, Burger King, or KFC have delivery services in Bangkok?), pinto delivery services had fallen out of popularity for years. But the nostalgia trend of the last decade had seen the resurgence of small food services in the city that specialize in retro, home-style dishes—the comfort foods mom used to make. Not surprisingly, pinto services are now back in full swing, delivering the Thai equivalents of the American macaroni and cheese, chicken fried steak with white gravy, baked ziti, meatloaf, pot roast, or chicken-broccoli-rice casserole, to hungry Bangkokians across the city.

Nowadays, though, pinto operators hardly go around the neighborhood putting menu pamphlets in your mailbox anymore; they have taken to social media, refusing to be limited by geography. Instagram, currently the most used and the most effective visual marketing tool in Thailand, has become these operators’ advertisement platform. And thus far, no Bangkok-based pinto service, on or off Instagram, has received more accolades and celebrities’ endorsements or garnered more press coverage than Pinto by Chak, a pinto business that began in 2014 with just one man, Prachak Chomram, cooking and posting what he made on the popular social media platform.

Prachak’s emphasis—obsession, really—on the use of seasonal and artisanal ingredients and a straightforward, unpretentious approach to cooking have apparently struck a chord with Bangkokians. Starting with a small customer base on the city’s east side where Prachak lives, Pinto by Chak’s army of motorcycle dispatchers now deliver to nearly every part of Bangkok. The success has led to Prachak’s debut book, Kan Doen Thang Khong Pinto (The Journey of Pinto), that tells the story of how a boy from rural Isan ended up running a wildly successful pinto business in Bangkok. It also features several recipes.

Below are some excerpts from the book (my own translation with some explanations in parentheses).

“I grew up in a home where the smell of a charcoal stove and the smell of Mom’s food woke us up every morning. We would begin each day eating breakfast together as a family before going off to work or to school. There would always be a full samrap on the table: a soup, a stir-fry, a curry, something deep-fried, and—this was a must—relishes and assorted vegetables to go with them.

“I grew up in Buriram. I grew up a country boy, eating whatever everyone else in my village ate. Relishes—those were always a part of a meal. Blanched vegetables. Fresh vegetables picked off the vines on the fence or from the rice fields. The curries we ate were Isan-style curries—no coconut milk. The only times we would get to eat anything special would be when Mom made a trip to the town center.

“I liked to watch Mom cook. […] That was how I learned many of her cooking secrets. For example, I’ve learned [from her] that when you make lāp, if you mix fresh lime juice into the raw chopped meat then squeeze out the liquid, your lāp will taste better.

“Mom always fried up some short-bodied mackerels for us to eat with a shrimp paste-coconut milk relish and fresh vegetables like cauliflower florets and napa cabbage. My mother was from Isan, but, surprisingly, the flavor of her food was always balanced and subtle [not titillatingly spicy hot as Isan food is often painted in broad strokes to be ~Leela]. There were some dishes to which she’d added pla ra (Isan-style fermented freshwater fish ~Leela), but it was so subtle, so expertly seasoned we didn’t even know there was pla ra in them.

“My mother used to sell khanom jīn nām yā (fresh rice vermicelli drenched in fish curry ~Leela). She’d roam the rice fields with two bamboo baskets hanging from a rod on her shoulder. When some customers said they didn’t have cash, she’d simply write down what they owed and let them enjoy the food anyway. Later, they’d pay her back in fresh unhulled rice from their fields.”

“When I moved to Bangkok, I stayed with a friend whose mother was an incredible cook. She was very particular about the quality of her ingredients, from shrimp paste to fish sauce to all the other key ingredients. The family came from Trat, and they were spoiled for choices when it came to seafood and seafood derivatives. Eastern food balances the three flavors very well, and living with this family helped ‘train’ my palate.

“One day that friend talked me into opening a restaurant. […] The restaurant went very well. […] But one day, our chef decided not to come to work—just like that. So we had to get into the kitchen and do the cooking ourselves. […] That was when we found out that, hey, we could cook!

“They say the four most difficult (Prachak uses the expression “prap sian” which refers to something so difficult it “conquers the experts/teachers/gurus ~Leela) dishes are tom yam, Thai omelet, spicy basil stir-fry, and glass noodle salad. These are all common dishes that look easy to make and are easy to make, yet they aren’t easy to make well. Anyone who can master these four dishes is a good Thai cook.

“Pinto by Chak dishes are a unique fusion of the traditional Isan dishes that I grew up eating—the food my mother made—and typical Central dishes with an influence of the Eastern dishes I’ve learned from my friend plus the Southern dishes I learned to make when I worked in the South. Sometimes I mix a Southern dish with an Isan dish; sometimes I do a mash-up of a Central dish with a traditional Phuket dish. That’s how we end up with a variety of things that you won’t find anywhere else.

“When I travel overseas, I often ask people I meet there to name the dishes they miss the most when they’re away from their home country. If I ask the Thai people the same question, I believe they will name things like som tam, sour curry, red curry, relishes, and—this is definitely one of the answers—Thai omelet. And these things will have to be eaten with warm rice and nam pla phrik. That’s the only way to cure homesickness.”

Excerpts from The Journey of Pinto, Pann Books, Bangkok: 2015. The book is available at most major bookstores in Thailand.

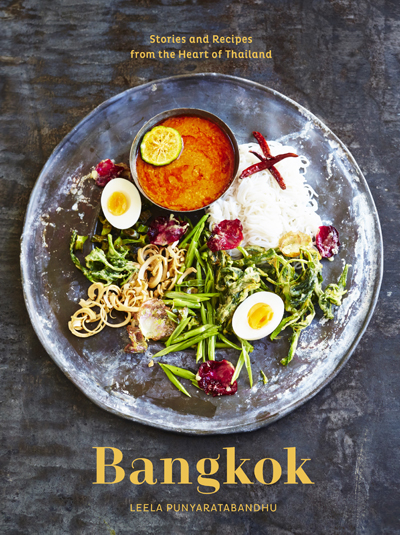

The recipe for the chicken curry you’ve seen above is my adaptation of Prachak’s recipe for chicken red curry with hearts of banana (these are the tender cores of banana tree trunks—not to be confused with banana blossoms or young green bananas) which he prepared for the hosts and crew of a popular Thai variety show on which he was a guest in late 2014. It’s also included in the book.

I needed to make some changes to the recipe because of the unavailability of 3 ingredients in my area: banana hearts, kaffir lime leaves, and lemon basil.

I see banana hearts sometimes at my regular South Asian grocery store, but most of the time, they’re nowhere to be found. I’m thinking that’s the case with most of you as well. With the main star of the show absent, I was left with two most promising understudies: canned hearts of palm in brine and white asparagus—the thick kind. I opted for the latter, because I don’t like the “can smell” and no matter how many times I rinse the hearts of palm, I can still detect it; YMMV. So I decided to go with white asparagus. Unfortunately, it wasn’t in season when I made this dish, so all I had were some slender stalks. They were tender, mild, and delicious, though—definitely a good option; they’re just too slender for you to cut them crosswise into thin slices like you would fresh banana hearts.

Kaffir lime leaves are usually available, but, on the day I made this curry, they weren’t. So I didn’t use them.

As for lemon basil, I can’t find it in my neck of the woods even in the summer. The only way I can get my hands on some lemon basil is for me to grow it myself. So, I used a combination of Thai sweet basil and fresh oregano which, according to one of my readers, Naphat, mimics the scent of lemon basil leaves quite well (thank you, Naphat!). If you can find fresh lemon basil, however, you really want to use it.

Note that the chicken is cut into smaller bone-in pieces with the skin on. This practice is typical in Thailand—the norm—especially when it comes to a rural, home-style curry such as this. Hacking up a whole chicken with a cleaver may be a pain in the rear end, but you will be rewarded with much more flavorful curry broth. This is a very delicious curry that Prachak and I would like to encourage you to try.

- One 3- to 3.5-pound chicken, preferably free-range

- ¼ cup prepared red curry paste (use half if heat is an issue)

- 1 cup coconut cream (the thick part that rises to the top of the can)

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 5 kaffir lime leaves, torn and bruised (I couldn't find them, so I didn't use them.)

- 1 tablespoon palm sugar (Prachak's recipe calls for granulated sugar.)

- 3 cups coconut milk

- One full-length banana heart (cut it crosswise into thin slices, soak them in acidulated water to minimize oxidation, drain well, and use a chopstick to remove the stringy resin as shown in the video I've linked to in the post) OR 1 pound white asparagus (trim off the tough ends and cut into 1-inch sticks)

- Fish sauce, to taste

- A handful of lemon basil leaves (or ½ cup packed Thai basil leaves and 2 tablespoons fresh oregano leaves)

- Cut the chicken through the bones into small chunks twice the normal bite size; set aside.

- In a large wok or Dutch oven, fry the curry paste with the coconut cream over medium heat until fragrant (it's okay if the cream doesn't split; if you use canned coconut cream, it probably won't). Add the chicken, salt, kaffir lime leaves, and sugar; continue to cook, stirring often, until the chicken is fully cooked, about 20 minutes (if the mixture gets too dry (likely the case if your wok is shallow and wide), add some of the 3 cups coconut milk to keep the sauce from scorching).

- Add the (remaining) coconut milk and cook the chicken until it's tender but still firm, about 15 minutes longer. Add the banana heart slices and more water, if necessary to keep everything barely submerged, and cook 10 minutes longer (2 minutes, if you use asparagus).

- Taste for seasoning; add fish sauce to taste.

- Take off the heat and stir in the lemon basil.

[…] home-style dishes? (The same scenario applies to catering services; we’ve seen some examples of […]