Songkran, Thai New Year, means different things to different people in Bangkok. To many, it’s the time to get out a plastic water gun along with a bucket of water and talcum powder, to wrap their cell phone in a plastic bag, and to take to the streets for some serious water-fighting fun. To just as many, it’s the time to go back to wherever home is and spend the days off with the loved ones they don’t get to see often the rest of the year. To some, it’s time to visit older relatives to wish them health and ask for their blessings in return. To some, it’s time to enjoy—even just for a few days—Bangkok without the usual around-the-clock traffic jam with many of the people visiting their homes upcountry.

I detest the water fight thing. I always have. I always will. So whenever I spend Songkran in Bangkok, I never leave home. I stock up on the basic grocery items in advance to last me for 3-4 days, and I don’t set foot beyond the threshold of my front door. I’m doing that right now.

But Songkran, to many Bangkokians, is the time to enjoy the fact that khao chae, a set meal of rice in iced flower-scented water with assorted accompaniments, can be found in various restaurants around the city. This is the once-a-year event that Bangkokians always look forward to. I’ve been getting my fill of this elegant, nostalgic seasonal offer, so as I’m sitting here under self-imposed quarantine, I’m not craving khao chae. I’ve been doing some thinking about it, though.

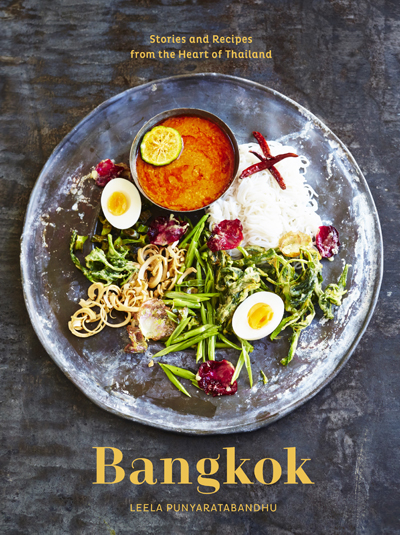

As you probably know, my new book, Bangkok, comes out around this time next month. And whenever I think back to the time when the recipe for khao chae almost didn’t make it into the book, I have a weird stomach-sinking feeling. It was a close call.

A book can only contain so many recipes. That’s a hard fact. Unlike a blog which is an ongoing, ever-expanding entity, a book is meant to be an anthology—a finite snapshot. And even though this is where its beauty lies, this is also where its limitations are most obvious. My book contract allowed for the length of about 350 pages; I couldn’t possibly fit everything I wanted the readers to know in that limited space. So I had to pare down—way down—my list of recipes and make sure I hit a right balance of all things that represented the food of Bangkok. A lot of thought went into that painful process.

I recently compiled a list of places to visit and things to eat in Bangkok for a friend who is going to spend just a little over a week there later this year, and the feeling I had when I was doing that was identical to the feeling I had when I was finalizing the recipe list for Bangkok cookbook. Trying to fit all the places in Bangkok that I want him to go and the foods I want him to experience into a week-long schedule was heartbreakingly difficult.

How do you fit a whole ocean into a shot glass?

I shudder thinking about that brief insane moment when I actually took khao chae off the list. Why? I knew from experience it would be a hard sell. Khao chae is an acquired taste. For what my experience is worth, nearly everyone who has promised me they can handle “challenging” Thai food, when in the presence of khao chae, cries “Uncle!” faster than you can say “deep-fried shrimp-paste balls.” Many—and I never understand this—equate an ability to appreciate Thai food with an ability to handle hot, spicy, and funky things or ingredients like blood and innards. In the context of Thai food, that is not the mark of connoisseurship at all. Khao chae, for example, isn’t spicy, but unless you grew up eating it, this set meal is going to be a learning curve.

Khao chae is not only challenging to eat (also there’s some etiquette rules involved which I’ve talked about in the book), it’s also challenging and time-consuming to make, requiring a very long ingredient list and multiple steps after which there will quite a few dirty dishes to watch. The inflexibility of what has become a canonized form of this set meal means everything needs to be just so in order for the Bangkokians to look at the recipe and go, yes, that’s how it’s done. This means the recipe would span at least 3 pages—I knew it would and, sure enough, it did. A photograph quota was another factor. This is one of the things every author has to negotiate with her publisher very carefully, weighing it against the other factors that affect the production cost. In the end, there’s always a limited number of photographs each cookbook is allowed to have after a long process of negotiation—of giving and taking. With khao chae being so little known outside Bangkok, I knew I would have to spend the photo quota on this one—and I did. In the context of cookbook making, this would, therefore, be a very, very costly recipe. And it’s the one recipe in the book that I was certain that most people, with the exception of those who truly get Thai food, would regard with suspicion, trepidation, and reluctance more than they would with unbridled excitement.

But with khao chae being so loved by Bangkokians and so tightly connected with the Bangkok eating culture, how could I not include it in a book that’s supposed to celebrate and honor the culinary heritage of one of the best food cities in the world?

So in the end, khao chae made it into the book. And if I had any one wish on this Thai New Year Day, it would be that people get excited about making and trying this dish and that they come to love it as much as the Bangkokians do. My wish, in other words, is to be pleasantly surprised.

Related Posts:

A Khao Chae Story

The Songkran Goddess Who Likes Blood

The Songkran Goddess Who Likes Bananas

A Place in Bangkok Where You Can Have Khao Chae

Comments are closed.